More Than A Conviction: Report

Stories of Children Sentenced to Life Without Parole in Illinois

By Michele Kenfack, Ph.D. and Corinne Kannenberg, Ph.D.

February 2025

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

After Illinois abolished its parole system in 1978, 104 children in the state were sentenced to die in prison. In 2012, a turning point occurred, when the U.S. Supreme Court mandated new sentencing considerations for children in Miller v. Alabama. Since that decision, many of the people who were sentenced as children to life without the possibility of parole in Illinois have been released, but a number of them remain incarcerated. All of these people are more than their convictions and have unique and valuable contributions to make to their families and communities.

This report uses quantitative data from the Illinois Department of Corrections and Northwestern University’s Bluhm Legal Clinic and qualitative data from interviews with some of the people formerly and currently sentenced as children to life in prison. It sheds light on the traumatic effects of lengthy incarceration and on the positive impact people who served decades behind bars can have on society. Children’s brains are still developing and require a different approach from the criminal legal system. The report recommends that people serving life sentences be given a chance to show their rehabilitation, and that those who have been released be given opportunities to promote well-being and healing, and prevent future harm.

INTRODUCTION

The first juvenile life without parole (JLWOP) sentence was handed down in Illinois in 1979. Subsequently, over 100 children were sentenced to die in prison. Some, like Joseph and Wendell, have been released. But others, like Yank, are still serving this extreme sentence.

This report details the lives of some of the 104 people who received JLWOP sentences in Illinois. It focuses on their childhoods and backgrounds, incarceration and experiences, and for those who have come home, reentry journeys after decades behind bars.1

Highlighting the unique experiences of those sentenced to die in prison as children, this report underscores the impact of adverse childhood experiences on children’s development, the importance of support during incarceration, and the value of reentry resources in helping returning citizens succeed and thrive. It also emphasizes the enormous contributions that people who were once serving JLWOP sentences have made to their families and communities upon returning home from prison. Their experiences underline the tremendous monetary and social costs of sentencing young people to a lifetime of incarceration.2

This report also details the lives of those who are still serving JLWOP sentences in Illinois. These people yearn for opportunities to demonstrate their growth and to positively impact their communities.

Altogether, these stories serve as powerful evidence of the harm caused by JLWOP sentences. They also reinforce existing research that shows that extreme sentencing practices do not promote public safety. In fact, harsh sentences divert resources from public-safety programs, including violence prevention and early childhood programs that have better records of reducing criminal involvement.3

Finally, these stories highlight young people’s capacity for growth and change and illustrate how lengthy incarceration deprives society of the valuable contributions people serving extreme sentences could make if they were returned to their families and communities.

This report and its accompanying narratives are part of a two-year storytelling project on juvenile life without parole in Illinois, funded by the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) Leading Edge Fellowship, Restore Justice Foundation, and the Mellon Foundation.4

This storytelling project focuses on people given JLWOP sentences as defined by the U.S. Supreme Court, meaning they were sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for offenses that occurred when they were 17 or younger.

HISTORY OF JUVENILE COURT IN ILLINOIS

Historically, Illinois was a leader in treating children differently than adults. The Illinois Juvenile Court Act of 1899 created the country’s first Juvenile Court in Cook County, a major breakthrough in the history of the United States legal system. This juvenile court was the hallmark of a juvenile system that had “the goal of diverting youthful offenders from the destructive punishments of criminal courts and encouraging rehabilitation based on the individual juvenile’s needs. This system was to differ from adult or criminal court in a number of ways. It was to focus on the child or adolescent as a person in need of assistance, not on the act that brought him or her before the court.”5

Acknowledging that children are developmentally different from adults and should be treated as such in the criminal legal system, the new juvenile court focused on transformation rather than punishment.6

However, in the “tough-on-crime” era of the 1980s and 1990s, the rhetoric around young people completely changed. The idea that children convicted of crimes may be irredeemable and the rise of the belief in so-called “superpredators” fueled policies that permitted — and, due to mandatory minimum statutes, often required — judges to sentence children to die in prison. Without any opportunity for release, people who were sentenced as children are denied a chance to demonstrate that they have grown and can contribute to society and their communities in meaningful ways.

As of 2024, approximately 2,500 children have received JLWOP sentences in the United States.7

While this project focuses only on people impacted by the U.S. Supreme Court’s definition of “juvenile,” it is important to note that other young people, aged 18-25, also received and are still serving life without parole (LWOP) sentences in Illinois.

JUVENILE LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE IN ILLINOIS: A DATA SNAPSHOT

The 104 children sentenced to juvenile life without parole in Illinois counted in this study ranged in age from 14 to 17 years old at the time of the crimes for which they were convicted. This includes 18 children who were 14 or 15.8

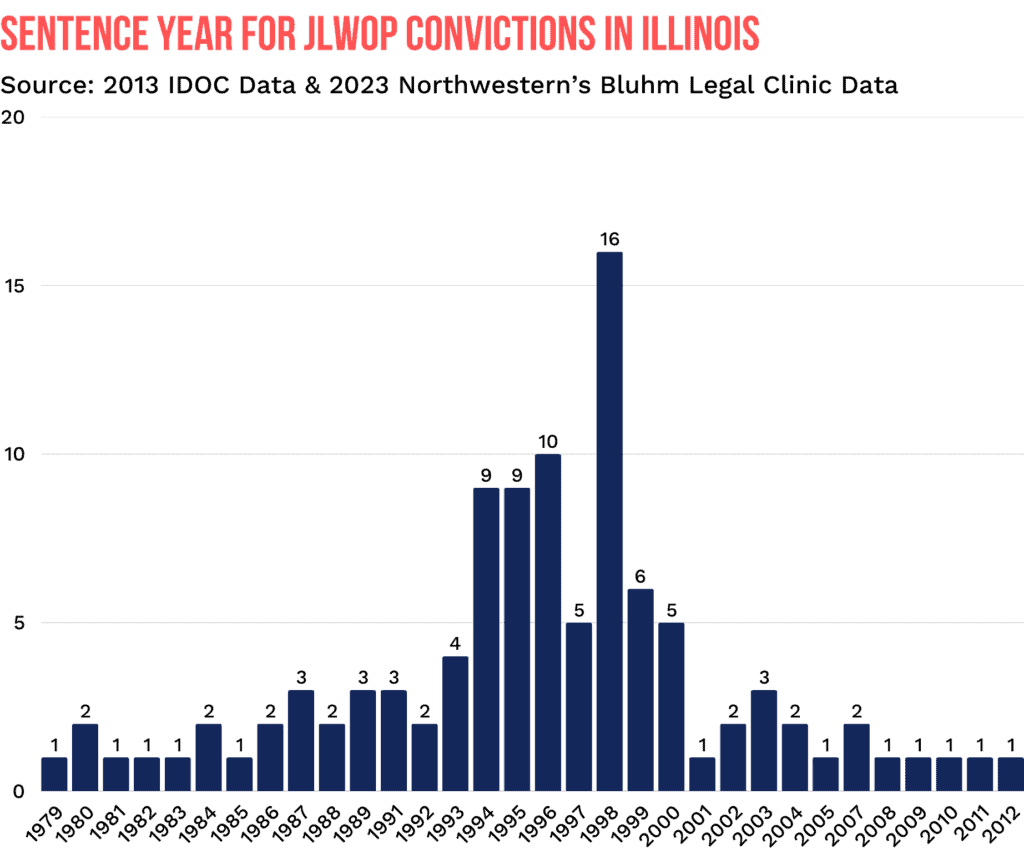

The data available indicates that the first JLWOP sentence in the state occurred in 1979, with a heavy concentration of JLWOP sentences being handed down between 1993 and 2000 (particularly 1998) at the height of the “tough on crime” era.9

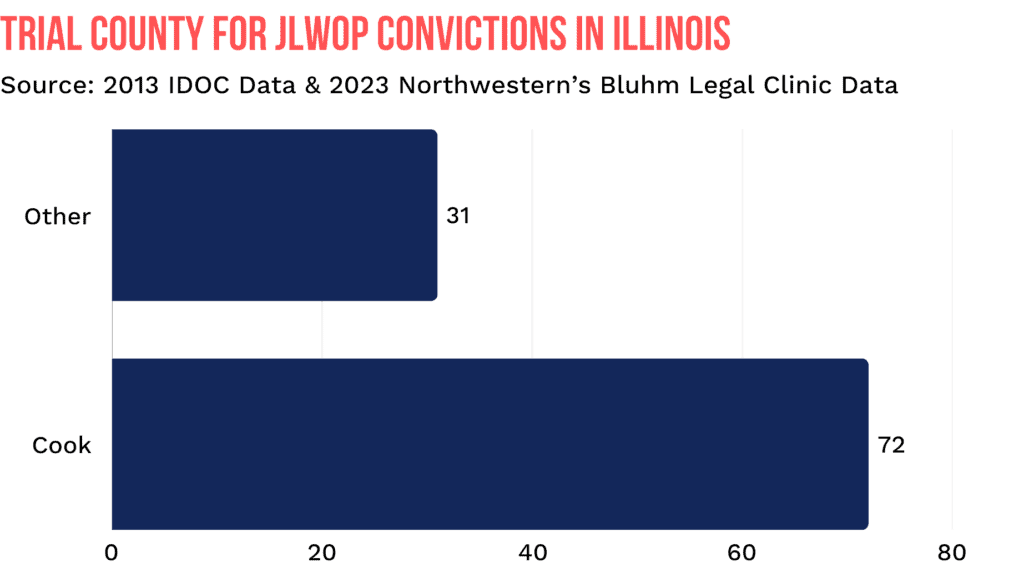

By a very large margin, most JLWOP sentences in Illinois were given by judges in Cook County, which includes the city of Chicago.

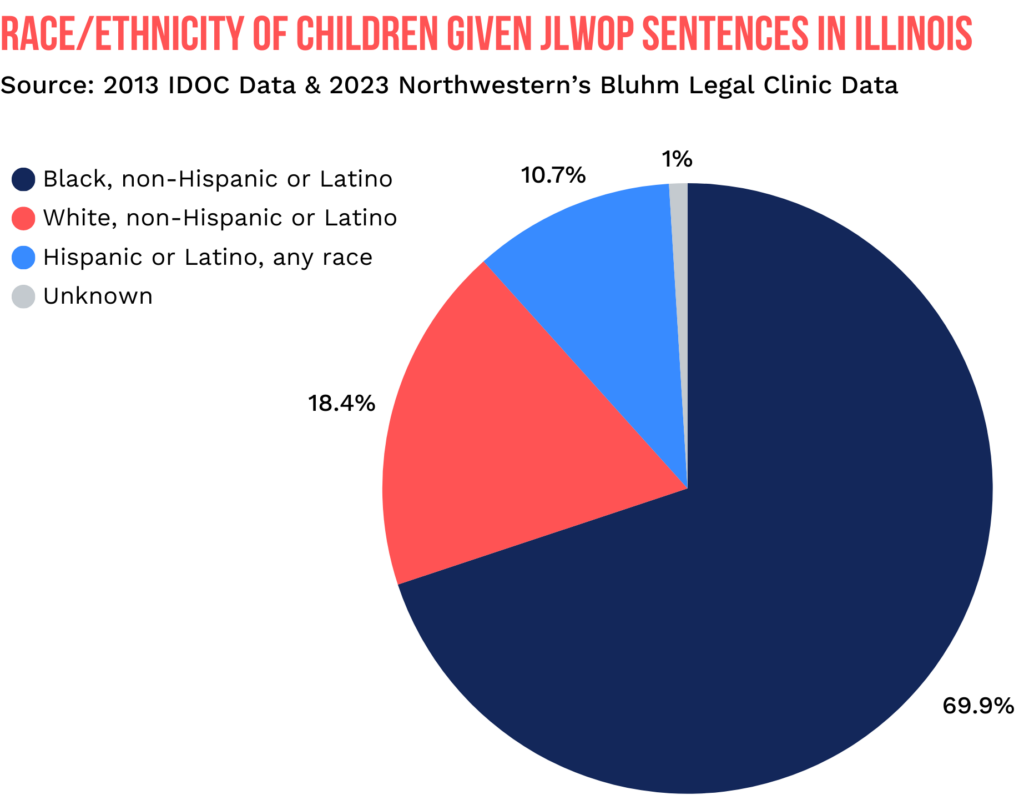

The data available shows significant racial disparities in incarceration – most people sentenced to life in prison as children in Illinois are Black.

Black people make up the majority of people sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for crimes that occurred at the age of 17 or younger in Illinois.

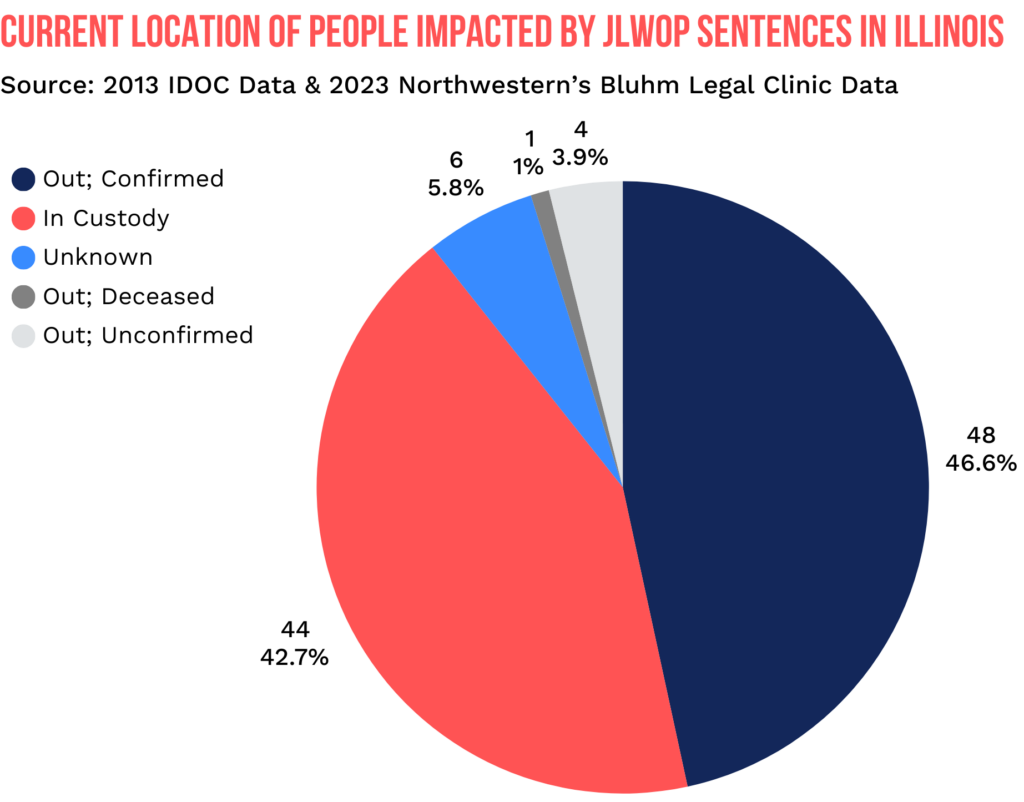

In 2012, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) ruled in Miller v. Alabama that mandatory JLWOP sentences are unconstitutional for people who were under 18 at the time of the crime. In 2014, the Illinois Supreme Court decided in People v. Davis that the ruling in Miller applied retroactively statewide. That decision was mirrored two years later in the 2016 SCOTUS ruling in Montgomery v. Louisiana, which determined that Miller applied retroactively nationwide. Following these court rulings, at least 70 (67%) of those who previously had JLWOP sentences in Illinois have been resentenced, although some were resentenced to discretionary life sentences. At least 49 (47%) have been released from prison as of October 2024.

At the time of this report’s writing, around half of the original 104 people sentenced to JLWOP in Illinois had been released from prison.

METHODOLOGY

The qualitative analysis in this report is based on interviews with 38 people (of whom 37 were male, 1 female) conducted between December 2022 and October 2023, representing approximately 40% of the total JLWOP population in Illinois. 18 of those interviewed are formerly incarcerated and had been released from prison at the time of the interview, and 20 are currently incarcerated.

In addition to people who served or are currently serving a life sentence, this report includes interviews with 9 family members of people who were formerly incarcerated.

Interviewees were given the option to remain anonymous for any reason and were also informed that they could decline to answer any question or stop the interview at any time.

Interviews with people who were formerly incarcerated and their loved ones took place in person, if possible, or over Zoom. Except for one, all of the interviewees who were formerly incarcerated lived in Illinois at the time of the interview. The loved ones interviewed for this project resided in Illinois and out of state. Interviewees provided written consent to be interviewed, recorded, and named in the project (if applicable).10

Demographics11

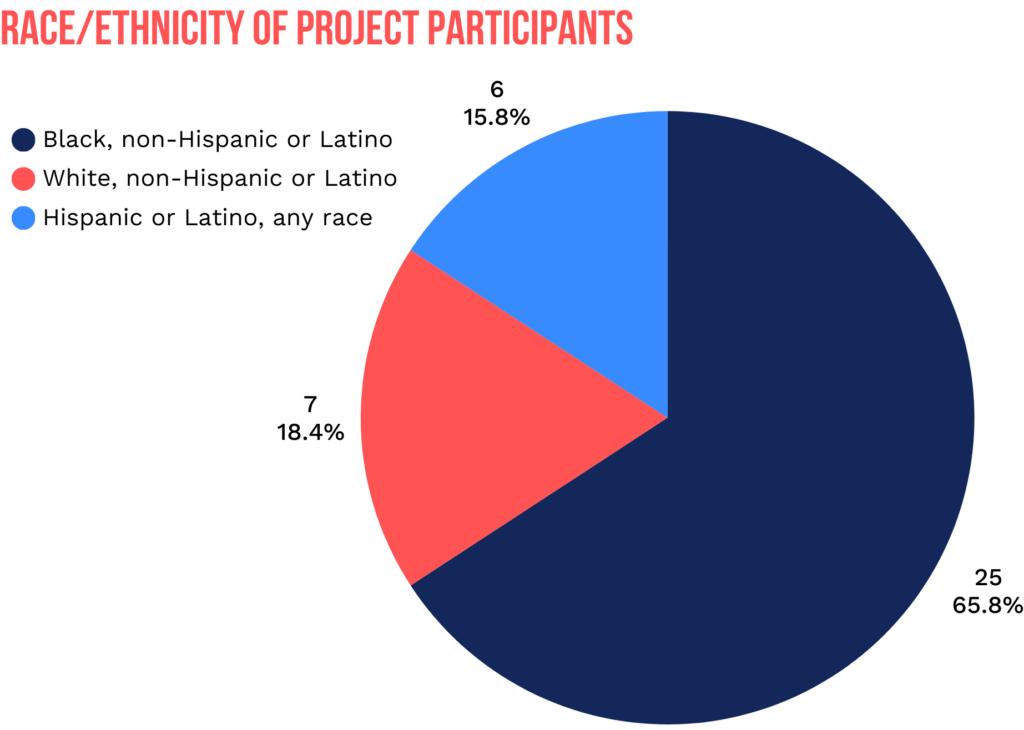

Restore Justice’s More Than a Conviction project participants roughly mirror the racial and ethnic breakdown of all those sentenced to JLWOP in Illinois, with a significant majority being Black.

LIFE BEFORE INCARCERATION

There is a strong correlation between traumatic events during childhood (0-17 years), officially called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and incarceration.12 Such experiences impact a child’s brain development and general health, which can lead to mental illness, substance use disorder, physical disabilities, and other long-term negative impacts on health and well-being. The overwhelming majority of people sentenced to JLWOP in this study reported physical or mental abuse and/or exposure to addiction and violence from a young age. In their childhood and early teenage years, many project participants reported exposure to one or several developmental risk factors for criminal behavior. For example, Jacqueline M., who was sentenced to JLWOP at age 15, said, “My stepfather was a gang lord; my mother was the wife of the gang lord, and she was also a victim of violence … I grew up around domestic violence, I had an abusive stepfather, who abused us, physically and sexually.”

Many participants reported that abuse at home prompted them to spend significant amounts of time with their peers. For some, this left them susceptible to peer pressure and even gang involvement. Jamie J. explained, “Some of my peers were affiliated with gangs, some sold drugs. I became entangled in that.” Kevin M., another interviewee, concurred: “Chicago was extremely violent; there were drugs everywhere. There were gangs everywhere, and it was not easy not to be affiliated when everybody was.”

This pervasive community violence becomes even more alarming when contextualized in the broader picture. Higher rates of violence are often linked to community disinvestment, as areas experiencing higher economic neglect tend to have higher crime rates due to poverty, unemployment, and social instability, which creates a perpetuating cycle. These neighborhoods have suffered from a legacy of discriminatory public policies contributing to victimization, trauma, and retaliation, creating the conditions for violence while lacking the community support to help them heal.13

ACEs also impacted project participants’ academic performances. Corey J. revealed that “the only time [he] could really get some peace and some sleep was during class, and that caused disruptions, and actually, problems at school.” Indeed, research findings associate children experiencing greater numbers of ACEs with negative school outcomes.14

Some participants reported that they started skipping school until they were finally expelled, while others dropped out altogether. Most project participants dropped out of school between 9th and 11th grade. A few were juniors or seniors in high school when they were charged with serious criminal offenses that disrupted their education.

These stories support the concept of the school-to-prison pipeline, which refers to policies and practices that push children out of the classroom and into the criminal legal system.15

One such practice is the zero-tolerance approach, which enforces strict consequences for certain actions, regardless of severity or circumstances. This approach, along with an increased presence of law enforcement in schools and decreased school funding, has generated (and continues to generate) negative student outcomes, including suspension, expulsion, and increased contact with law enforcement. Students of color face disproportionately harsher punishments and, as such, are more likely to be involved with the criminal legal system.

Nick M., who was incarcerated for over two decades, noted that “society cannot expect young people to succeed when they do not feel safe at home and in school.” He believes that the lack of consideration and empathy in schools, particularly for students of color, is one of the primary reasons children become isolated, face suspension or expulsion from school, and later end up in the criminal legal system.

SENTENCING

All participants in this project were under 18 at the time of the offense for which they were sentenced to life without parole. Fifty percent were 17 years old, and the rest were between 14 and 16.

The majority of project participants (approximately 74%) were sentenced in Cook County. Other sentencing counties included Du Page, Kankakee, Menard, and St. Clair. Most sentences were handed down between 1991 and 1999, with the highest number, 6, in 1998. These trends among project participants also reflect the statewide trends.

Interviewees shared some common experiences in sentencing, even though their ages and the year and/or location of their sentencing differed.

A few interviewees reported that during trial and sentencing procedures, prosecutors asked the court to sentence them to death. “I remember the state’s attorney asking for the death penalty,” Nelson M., who was sentenced in 1995, said. “And my public defender was so ignorant he couldn’t even stop the motion. It was the judge that said, ‘How old are you? How old are you? No, motion denied he’s not old enough.’” Wendell R., sentenced in 1994, had a similar experience. He noted that “the prosecutor asked for the death penalty, but I wasn’t 18 at the time of the crime, so I couldn’t get the death penalty here [in Illinois].”

Although the death penalty for children under 18 was not banned nationally until the 2005 SCOTUS decision in Roper v. Simmons, Illinois did not permit the execution of children at any point in its history. The accounts of prosecutors nevertheless asking for children to be sentenced to death speak to the harshness of the “tough-on-crime” rhetoric of the mid-1990s.

Interviewees described the way in which this rhetoric was reinforced by extreme animosity during trial and sentencing. Michael W., who was sentenced in 1991, shared that he felt as though the prosecutors depicted him to be so criminal that he was inhuman. “In court, they made me out to be the monster I knew I wasn’t,” he said. “And I’m hearing it, and I’m like, that wasn’t me. … The person you’re describing here in this courtroom is not me.” William N., sentenced in 1996, felt as though the prosecutors looked at him during the proceedings as if to say, “‘You’re going down,’” taking pleasure in the extremity of his charges and sentence.

Mandatory Sentences

Mandatory life without parole (LWOP) sentences are required for certain convictions, as designated by state law. Mandatory sentences must be imposed regardless of a judge’s opinion and, in many states, regardless of the age of the defendant. Discretionary LWOP sentences, on the other hand, can be optionally imposed by a judge after careful consideration of mitigating factors, a person’s role in the crime, and their potential for rehabilitation.

In Illinois, during the tough-on-crime era of the 1980’s and ‘90’s, a first-degree murder conviction in a case with more than one homicide carried a mandatory minimum sentence of natural life imprisonment, regardless of the age of the person convicted. Several project participants received mandatory JLWOP sentences for this reason, even though they recounted that their judges were reluctant to inflict such a punishment. At the end of his trial in 1994, Wendell R. recalled the judge explaining that he wouldn’t give him a natural life sentence if he didn’t have to. Similarly, Kevin M., sentenced in 1999, said he never forgot the judge’s words as he read the verdict: “Unfortunately, legislators do not allow me to give you anything but natural life or the death penalty. My hands are tied.”

The words of Wendell’s and Kevin’s judges underscore the importance of non-mandatory sentencing statutes. When mandatory minimum sentences are determined by lawmakers, the ability of judges to make individual sentencing determinations based on specific circumstances is severely curtailed. The U.S. Supreme Court recognized the need for judicial discretion in their landmark 2012 decision, Miller v Alabama, which abolished mandatory LWOP sentences for children under 18. In the case Montgomery v. Louisiana, the U.S. Supreme Court made Miller retroactive nationwide, and concluded that LWOP sentences should be “uncommon” and reserved only for “those rare children whose crimes reflect irreparable corruption.”

Accountability Theory and Felony Murder

Several interviewees received LWOP sentences under Illinois’ theory of accountability and the closely related felony-murder rule. These legal frameworks contribute to lengthy prison terms by making it easier for prosecutors to convict people of murder regardless of the extent to which they were involved in a crime.

According to Illinois’s law of accountability, a person can be arrested, charged, and convicted of a crime they did not personally commit or even plan, agree, or intend to commit, and regardless of whether they were present for the crime. Under some circumstances, this law allows someone to be convicted for another person’s criminal acts if they acted as the lookout for the criminal offense, failed to report the incident, or accepted illegal proceeds resulting from criminal actions, among other actions.

The law of accountability is a legal theory the state uses to convict people of crimes with which they were associated but did not commit. Accountability is not the definition of a criminal offense, but rather is applied to people who were “accessories” or “passive participants” in a crime.

Wendell R. was sentenced to life in prison under accountability theory. When he was 17, some of his belongings went missing. The person he thought had stolen them was later killed, and Wendell was accused and convicted of murder. “I didn’t shoot anyone; I didn’t even have a gun, but I did point that man out, and he lost his life,” he said.

When Marshan A. stole a van in 1992, he didn’t know it would lead to murder charges. Yet, two years later, he was convicted and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole because those who rode with him in the stolen van that day killed two people. Marshan was convicted not only under the theory of accountability but also under the felony-murder rule. This rule states that a person can be found guilty of felony murder if they or a co-defendant causes a death during the course of an underlying forcible felony. Marshan admits that he stole a van. He was shocked by the natural life sentence he received for aiding and abetting a home invasion that resulted in a double homicide. “I just stole a van. I didn’t kill anybody. I didn’t hurt anybody. I didn’t have a weapon. I didn’t even know [those riding with me] were going to kill anybody, but [prosecutors] were trying to send me to prison for the rest of my life.”

Young people are particularly vulnerable to being charged under accountability theory or the felony-murder rule, given that they are more likely to act in groups, more susceptible to peer pressure, and less able to anticipate or fully comprehend the consequences of their actions.16

These legal mechanisms can be used as bargaining chips in plea deals, resulting in children receiving lengthy terms of years or de facto life sentences.

COPING WITH A LIFE SENTENCE

“[My co-defendant] and I were outside the courtroom with about 15 to 20 other people, and we were joking. When people asked us why we were in court, we were just like, ‘We are getting sentenced today.’ And when they asked how much time they were going to give us, we were like, ‘natural life without parole.’ We did not understand what was happening. Literally, we might as well be talking about a new episode of ‘Cheers’ coming on that night,” Eric A. explained. Several other project participants were in similar states of confusion or denial upon hearing that they were sentenced to die in prison. “When I was in the county jail, guys who were older than me and who had been there longer than I had tried to tell me that I would be in prison forever. I didn’t understand,” John H. said. At 14, John H. was one of the youngest people incarcerated for murder and awaiting trial. Even after the verdict, he still couldn’t grasp the full meaning of his natural life sentence.

Many project participants and their families were in disbelief that it is legal to sentence someone under 18 to die in prison in the U.S. They described the difficulties of coming to terms with their natural life sentences and of coping with the reality of such an extreme punishment. For Nelson M., having a life sentence was akin to “being covered with a sopping wet blanket.” For Jay J., it was like “being saddled with the whole world upon you.” John H. said he later understood things would not improve for him. Kentay R. realized, “My young life was over, I wouldn’t have an adult life on the outside, I would never see my family again.”

Despite the dire circumstances, most interviewees refused to accept their fate, choosing instead to hold on to hope. Nick M. explained that he spent “hours talking” with one of his friends, “trying to figure out a game plan … with the hopes that things were going to change for juveniles.” Kevin M. shared a similar train of thought. “Even without an out date, I carried myself as if I had an out date. It was about ‘speaking’ my freedom into existence,” he declared. Ethan N., who has been incarcerated for almost thirty years, expressed the same feelings. “I never accepted my sentence. I mean, I am doing the time, but I never thought I would die in prison. I always believed I would return home to my loved ones.”

Religion became a source of comfort for many interviewees. “I told myself that maybe God had plans for me that were beyond my understanding. I was doing so many things and I wasn’t listening to his voice. I decided to listen to God’s voice, and from then on, I looked at my incarceration as a spiritual punishment more than anything else. And that’s how I was able to find solace,” Jamie J. said.

Others took advantage of every available learning opportunity to keep their minds busy. Kevin M. reported that he became an avid reader and took a variety of college classes, including law, finance, and computer science when given the opportunity. “Learning was the main thing that helped me do my time without losing too much of myself,” he stated.

INCARCERATION EXPERIENCES

People sentenced to JLWOP have unique perspectives on incarceration for several reasons. For one, they entered the carceral system as children, either through juvenile detention centers or directly into county jails with adult populations. They were also among the youngest people incarcerated in the state prisons where they served the early years of their sentences, and they entered prison with the harshest sentences possible short of the death penalty.

In Illinois, those under 17 at the time of their arrest were placed in juvenile detention. In Cook County, the Juvenile Temporary Detention Center, commonly known as the “Audy Home,” housed children between the ages of 10 and 16 awaiting adjudication of their cases. Those who were 17 and older were sent to the Cook County Jail. Interviewees who spent time at either of these facilities described the harsh conditions and extreme violence that characterized both places. Eric A., who was taken into custody at age 15, said about the Audy Home, “The juvenile detention center was a violent place with very little reprieve or respite. It initiated me to prison life.”

Education

The widespread inaccessibility of substantive programming opportunities like education and vocational training was a common theme in interviews for this project.

Two major factors created the severe shortage of meaningful learning opportunities for people sentenced to JLWOP in Illinois. First, many prisons in Illinois restrict access to programming opportunities for people with lengthy sentences. Second, the removal of federal funding for postsecondary education for incarcerated learners in 1994 led to the absence of college-in-prison programs in Illinois for many years.

Many maximum-security facilities in Illinois, where people with life sentences are most commonly housed, have only minimal programming, and so-called “lifers” are often excluded from participating in any available programming. This is not to say that programming was nonexistent; many interviewees reported receiving their GED and vocational certificates at some point during their incarceration. However, nearly all interviewees expressed frustration that they did not have access to more opportunities, a sentiment that is reflected in national studies of program opportunities in state prisons.17

Many interviewees described a widespread sentiment among IDOC staff that more advanced or comprehensive educational opportunities, such as in-depth training or higher education, were pointless for people sentenced to die in prison. James S., who served almost three decades behind bars, explained, “In maximum penitentiaries, they don’t try to educate anybody. You get the basics, and some people don’t even get the basics. Some people won’t be allowed to get a GED because of their sentence.” This mentality reflects a broader sentiment within the carceral system that education’s only purpose is to help people who will soon be returning home.

While studies show a strong connection between education and positive outcomes after release, limiting access to learning based on sentence length is harmful and shortsighted in two ways. One, it overlooks the reality that even people with life sentences may be released from prison due to wrongful convictions, appeals processes, court decisions, or legislative changes. Two, it ignores the positive impact education can have more broadly on a person’s well-being, self-worth, and growth, separate from reentry or career aspirations.

Although access to programming has improved somewhat over the years, a quality education (academic or vocational) remains out of reach for a significant portion of people serving lengthy sentences. Jermaine J. noted that he was asked about his sentence directly when he expressed interest in vocational training at Menard Correctional Center, and he was quickly denied participation when it was clear he had a life sentence. It wasn’t until he was resentenced under Miller and transferred to Kewanee Life Skills Re-Entry Center, a minimum-security facility focused on preparing people for reacclimation outside of prison, that he was able to get substantial training. But by that point, it seemed too late. “I felt like I was behind, even though I was sitting for a long time. I felt like I was behind insofar as I should have more trades,” Jermaine said.

Educational opportunities for people in prison were also significantly affected by the federal Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, commonly referred to as the 1994 crime bill. One of the provisions of the bill made incarcerated learners ineligible for crucial need-based Pell Grants, which substantially changed the landscape of college-in-prison programs during the 1990s and 2000s. Marshan A. recounts his experience trying to begin a college program in the same year the bill was passed: “I got to Pontiac [Correctional Center] in ’94. … They called me over to interview and fill out the paperwork and all that stuff [for college]. And then like literally like a month or two later, that’s when the government stopped the Pell Grants and the Department of Corrections decided to remove the college programs from the maximum-security prisons in Illinois,” he explained.

Since 2023, some people in prison have become eligible for Pell Grants again.18

For many of those serving JLWOP in Illinois, however, lacking that opportunity for most of their sentence made higher education unattainable.

Food and Health

Project participants unanimously agreed on the poor quality of food in prison and the accompanying difficulty of staying healthy. They spoke of spoiled and improperly cooked food, and rotten, moldy, or vermin-infested fruits and vegetables. One notable and disturbing exception was associated with the food provided on days that executions took place in the prison. Wendell R. noted, “Every time there was an execution in the facility, they fed you really, really good. It was burgers and fries, fried chicken, and a big pack of cookies. But after they stopped executions [in 2011], food as a whole just got worse and worse.” In retrospect, he found the connection between better food and imminent death rather “eerie.”

Participants described the typical prison diet as high in sugar, salt, and refined carbohydrates. For them, eating while serving time was just about filling up their stomachs. Steven M., who served 25 years, detailed the options available during his time in prison. “The chow hall food was more nutritious than commissary food, but it tasted nasty as hell. People preferred commissary food, which is pretty much what you would buy from 7-Eleven or a gas station. We actually called it ‘gas station food.’ There were some sausages, chips, cakes, packaged tuna, packaged chicken, etc. None of these options was good, but you had to pick which one you would rather deal with.” Interviewees also pointed out that food quality has steadily declined over the years. Joyce H., who has been in prison for three decades and was working in the kitchen at the time of this survey, shared that “the food quality goes down every year even though the food budget goes up every year.”

These observations corroborated the findings of Impact Justice’s 2020 national investigation into prison food. This broad inquiry reveals that three out of four people were served spoiled food in prison. The study rightly describes food in prison as a “hidden punishment,” another way of stripping away the humanity of people serving time.

Depriving people who are in prison of nutrition does not just violate their constitutional and human rights to an adequate standard of living; it also creates a public health problem. Unhealthy and inadequate food fosters high blood pressure, kidney disease, diabetes, and other illnesses associated with poor nutrition. Yet, despite the widespread incidence of these conditions associated with poor nutrition in prison, the carceral health care system is extremely deficient.

Health Care

In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Estelle v. Gamble that failure to provide adequate medical care to people who are incarcerated as a result of deliberate indifference violates the Eighth Amendment.

Project participants underscored facilities’ inability to provide adequate medical care. “It’s always a fight to get some kind of treatment, or get some kind of help,” James S. said. Calvin B. confirmed, “Medical assistance is so bad I pray every day not to get sick.” Joyce H. recalled how three people he knew were sick but did not get appropriate medical attention — in these cases, timely cancer diagnoses — because of the cost. They were told the institution could not afford to provide them with treatment. Yank C., who is currently incarcerated, shared his personal ordeal: “I have high blood pressure and acid reflux; I suffer from degenerative disk disease, and I am hearing impaired. In addition, my finger is permanently damaged because when I broke it, it took over two months for the health care staff to send me to an orthopedic doctor.”

People who are incarcerated are more likely to suffer from chronic health conditions, substance use, and mental health disorders. A 2020 Prison Policy Initiative report identifies chronic health conditions as one of the leading causes of death among older people in prison. Another report published in 2022 exposes alarming discrepancies between the medical conditions of people in state prisons and the U.S. overall general population. For example, the report outlines that the percentage of people suffering from asthma in prison (16.7%) is twice that of adults nationwide (8.0%). Similarly, Hepatitis C rates are significantly higher in prison (9.5%) than outside (1.7%).

Harmful Environment

The Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishment” suggests that people who are incarcerated must receive basic necessities, including a safe environment and an acceptable standard of sanitation. Additional international standards provide further guidance on humane prison conditions. For instance, Rule 13 of the revised United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules) of 2015 stipulates that “All accommodation provided for the use of prisoners and in particular all sleeping accommodation shall meet all requirements of health, due regard being paid to climatic conditions and particularly to cubic content of air, minimum floor space, lighting, heating, and ventilation.”

Project participants described living environments that sharply contrasted with these national and international guidelines. In addition to overcrowding, they decried poor ventilation, poor sanitation, and infestations of vermin and bugs, among others. Joyce H. noted that all the facilities where he was incarcerated in Illinois had something in common: “They were falling apart.”

People also identified violence as one of the major issues behind bars. They described confrontational interactions not only with staff, but also with other incarcerated people. Eric A. recalled that while in prison, he was not sure he would live past his 22nd birthday because of regular conflicts with other people who were incarcerated.

Interviewees reported a wide variety of inhumane, cruel, and degrading treatments. A number of them had to do with basic sanitation. Some respondents reported being denied access to showers, especially during lockdowns, while others reported seeing urine or blood in the showers. “During lockdowns, we could remain in the cell for six days and only take a shower on the seventh day,” John H. recalled. Lack of privacy in taking care of personal hygiene is standard in prison; toilets are generally located in cells with no sort of privacy screen, and showers are open and communal. Several respondents reported feeling embarrassed and deprived of their dignity.

Another way in which interviewees reported being humiliated was during shakedowns by the so-called “Orange Crush,” the tactical team in charge of searches of people and property.19

Project participants described the Orange Crush as cruel and ruthless. Nelson M. remembered how degrading the searches were. He described how people who were incarcerated were stripped and lined up: “Your hands are behind your back. And there’s another guy, and you got to be right up on him. So, basically, his hands are almost touching your privates and vice versa, and you got to be right up on him. And you’ve got to look down.” Furthermore, cell searches often resulted in people’s property and belongings being destroyed.

Many project participants also reported ill-treatment associated with racism and discrimination. For example, Nelson M. pointed out that Menard, located in Southern Illinois, “was openly racist.” Michael W. concurred. “Menard is worse than any penitentiary. [People who are incarcerated there] are regularly treated like cattle, especially people of color.” He recalled the everyday use of racial slurs by correctional officers as well as regular prejudicial treatment. “Say, like, a cell toilet don’t work. [Black people] get those cells until they get it fixed. If we go into the shower, most times we get the bad shower heads and stuff.”

Solitary confinement, or segregation, emerged as the most dreaded form of mistreatment among participants. Jamie J. unequivocally described it as his “breaking point.” Creating and following a routine was the only way he could cope with isolation: “I would work out in the room, then wash up, eat, do some reading or writing, and after that, I’d just wear myself out playing chess or praying. I did it every day, continuously.” Besides daily routine, mental escape was another coping mechanism among participants. Jacqueline M. explained, “Being incarcerated and being in confinement is like being behind double locks. It’s like being in jail inside of a jail. I could cry all day.” She further described her coping mechanism: “I built a fantasy in my head. I had a whole life in my head. I envisioned myself married with kids, having a job, going to the store, and driving my car. I lived my fantasy.”

Time in segregation can create or worsen mental disorders. It also increases the risk of self-harm and suicide, and project participants unanimously called for the discontinuation of this inhumane practice.

In addition to segregation, correctional facilities are regularly under “lockdown,” which refers to times when all residents are confined to their cells. All project participants expressed strong disapproval of the excessive use of lockdowns, and many reported physical pain and mental distress from months-long lockdowns, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. “I hated going on lockdowns because you couldn’t do anything. You had to find other ways to keep your mind active while you were idle. If people knew we were gonna be on lockdown for at least 30 days, the first week was really quiet, because guys had to get into lockdown mode mentally,” James S. remembered.

Community Behind Bars

Children who were sentenced to life without parole in Illinois grew up in prison, and many of them became family to each other. Those who participated in this project acknowledged that their brothers and sisters in prison provided much-needed guidance, nurturing and strengthening them. Eric A., who served time with two people who were his friends before their incarceration, stated, “We went through a lot together, in and outside of that cell. Prison can shatter people and relationships. We weathered the storm. These two are like my family.” A number of others who have been released echoed this sentiment. They shared that those who served time in prison with them, particularly those who were given lengthy sentences as children, remain an integral part of their lives. Unlike people who have never served time, they understand and can relate to each other. “With [my friends from prison], there’s no barrier. Anything they know, they pass it on immediately, and there’s no expectation because they know where I come from,” James S. commented.

MECHANISMS OF RELEASE

“Being in the cell 20 to 23 hours a day, every single day. No programs, no school, nothing! I will be lying if I say I never felt discouraged. I felt discouraged several times,” John H. said. The 2012 U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Miller v. Alabama brought a glimpse of hope to John and others who were serving what seemed to be an irreversible sentence. The vast majority of interviewees felt excited at the prospect of having a pathway to release. “When Miller came, it was literally like looking into the tunnel and seeing a crack. Like, ‘Is that a little light? Huh! I haven’t seen that before!’” Nelson M. recalled. John H. emphasized, “I was elated. Once we heard about it, we started thinking, ‘We are going home, soon we will be out there with our family.’” Some, however, were quite skeptical of Miller’s impact on their lives. “I was nonchalant about it. I thought, ‘We do not have a chance in hell,’” Michael M. declared. William N. thought it was “too good to be true.” Nick M. remembered some of his friends saying, “That is only for [Evan Miller, the petitioner in the case]; it is not going to happen to us.”

Those who were skeptical about Miller were not entirely wrong, especially because at first, the decision was not retroactive, meaning it did not apply to those who were sentenced before 2012. It became retroactive in Illinois in 2014 following the Illinois Supreme Court’s decision in People v. Davis, and nationwide in 2016 following the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Montgomery v. Louisiana. But even after retroactivity was established, it was not applied automatically. Rather, individuals had to petition for a resentencing hoping to receive a lesser sentence.

Miller simultaneously presented an opportunity and a difficult decision for some so-called juvenile lifers, as it forced those eager to prove their innocence to choose between pursuing an actual innocence claim or a Miller resentencing. All project participants in this situation selected to pursue resentencing opportunities under Miller instead of actual innocence claims because of the precarity of the latter option. For example, Wendell R., opted to take a 50-year sentence (to be served at 50%) for his second case rather than pursue an additional innocence claim, because it was a faster path to release. “I came home in January 2018 via Miller. It was something that I was so reluctant to do, but at the same time, it was a real-deal blessing in disguise,” Wendell said. William N. also accepted a 50-year sentence to be served at 50%, though he, too, wanted to pursue actual innocence. For William, resentencing meant “I was, like, a year and maybe a couple of months from going home,” William said.

In addition to Miller resentencings, clemency has also been an avenue for release for those with JLWOP sentences. Many interviewees did not explore this option because clemencies were so rarely granted that they considered the process a waste of money and time. “It didn’t seem realistic. So why put my mother through it and spend about $5,000 just like that? Until [Gov. Pritzker’s administration], you didn’t hear about people going home on clemencies. You heard about overturned cases, but not clemencies,” Nelson M. explained. Jamie J. applied for clemency twice, but his petitions were denied. James S. petitioned for clemency at the same time that he was pursuing a Miller claim. He was the sole project participant whose clemency petition was granted: he was freed during a wave of early releases that were meant to alleviate overcrowding in prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Seventeen people who participated in this project were granted shorter sentences, primarily through Miller resentencing, and were subsequently released. Their dreams of coming home finally became a reality after decades behind the walls of a prison. One participant was exonerated after coming home. He is among at least eight former “juvenile lifers” who have been exonerated. This puts Illinois “juvenile lifers” at a higher rate of exonerations than the general U.S. prison population; as of 2024, the national exoneration rate was approximately 4% for capital cases and 6% for people incarcerated at state facilities.

A few interviewees who are still incarcerated also received shorter sentences following the Miller decision and now have out dates. Joyce H. was resentenced to 60 years to be served at 50%, and is set to be released in 2031. Adam D., who was resentenced to 73 years to be served at 50%, has an out date of 2032.

However, resentencing hearings do not always result in lesser sentences. Some interviewees received long discretionary sentences from their resentencing judges. Vern M. was resentenced to life without parole, and is considering other avenues for release. Deon L. was resentenced to 40 plus 37 years, running consecutively, and is currently awaiting a decision for the petition he filed to oppose this de facto life sentence. De facto life sentences are considered “virtual” life sentences because they are so long that the sentenced person will likely spend most of their natural life in prison or die before their release.

Other participants, like Peter S. are still waiting for a resentencing opportunity with the hope of being granted relief. “To have this sentence reduced, giving me a light — something to look forward to — would be like being born again. I know I still have a life. There’s a whole lot I can still do. I would like to go back to school, drive trucks, and get into house rehabbing,” Peter said.

LIFE AFTER INCARCERATION

For those who spent decades behind bars, the joy of leaving prison and regaining freedom is often accompanied by emotional and practical barriers to their well-being.20

Project participants all underlined the challenges of social reintegration after lengthy incarceration, especially without a strong support system. They acknowledged that the road to rebuilding their lives, creating social networks, and giving back to their families and communities is hard and stressful, primarily because of daily uncertainties. Their achievements happened not thanks to but despite the carceral system.

Limited Resources

Interviewees did not feel well prepared to reintegrate into society, primarily because they had limited access to reentry programs in prison. In Illinois, there are only two facilities specifically geared toward reentry: Kewanee and Murphysboro Life Skills Re-Entry Centers. Unfortunately, not everyone can finish their sentences in one of these prisons.21

Beyond reentry centers, reentry programs are concentrated in a few minimum-security facilities and prioritize people with shorter sentences. Most participants in this project were released directly from medium- or maximum-security prisons with little or no reentry programming and, as a result, did not have opportunities to acquire the skills necessary to help them adjust to life after prison.

Participants also reported that the lack of resources or connections to resources posed a significant challenge once released. Joseph R., for example, was released from Stateville Correctional Center with a $40 regional train ticket and the threat of being found in violation of his mandatory supervised release (MSR) conditions if he did not reach the halfway house he was discharged to by 11 p.m. With the help of good Samaritans, Joseph was able to find his destination. However, the severe lack of support from IDOC in situations like this highlights the urgent need for more comprehensive reentry services — starting before release and continuing throughout the reentry process — to better support people as they transition back into society.

Mental Health

Incarceration is a traumatic experience that can negatively impact a person’s psychological and emotional well-being.22

The defining features of incarceration, including isolation, exposure to violence, and lack of mental health resources, can cause or worsen mental illnesses and exacerbate symptoms such as depression and anxiety. As noted by the Prison Policy Initiative, “Prison is basically a mental health crisis in and of itself, and too many incarcerated people contemplate and/or complete suicide.”23

Isolation and solitary confinement are particularly detrimental to mental health. According to a 2024 report by a coalition of legal and civil rights organizations, “Solitary confinement literally causes the brain to shrink, and it induces a broad range of severe harms, up to and including psychosis and suicide.” The report also explains that solitary confinement in IDOC prisons is “especially severe,” subjecting “prisoners to conditions and forms of treatment that go beyond being painful, unpleasant, and potentially harmful to being outright dangerous to prisoners’ mental health and well-being.”24

Lengthy stints in solitary exacerbate suffering and trauma, and after returning to society, formerly incarcerated people experience behavioral health conditions that impact relationships and social functioning. This includes disconnection from family, flashbacks, and hypervigilance. Judge Patrick Murphy, sitting in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Illinois, found that “prolonged isolation has negative impacts on incarcerated people, impacts which can last for years even after they are released from solitary.”25

Furthermore, according to a Journal of the American Medical Association study, exposure to solitary confinement during incarceration is associated with an increased risk of death during community reentry.26

Interviewees, who all spent decades in the carceral system, admitted that mental health issues were a significant obstacle toward reacclimation. Eric A. shared, “A lot of traumatic things happened to me; there’s a lot of damage that I try to cope with on a regular basis. The traumas I went through did a lot more damage to me in my ability to relate to people than I ever really could have understood if I had just stayed incarcerated.” Like Eric, Jamie J. also said he has post-incarceration-syndrome and finds it difficult to form and maintain relationships, mostly out of caution. “I am very careful. I don’t really go out. I just kind of stay at home to relax, watch a movie, or do some work.” He wants to avoid any problematic situations that could lead him back to prison.

Project participants also emphasized the difficulty of connecting with relatives and loved ones after years of separation. They have found it difficult to accept and give love and communicate their needs after being treated as less than human during incarceration. They also reported having a hard time making themselves emotionally available to repair broken bonds and (re)build relationships. James S. summarized the issue: “When you come out of prison, your conversations change, your relationships change. Some people who were alive when you went to prison are not alive anymore. It’s a journey with ups and downs; it’s all about communication.” Nick M. shared that after his release, he found himself “constantly wearing a mask of invulnerability,” following the advice he received in prison: “There is no emotion here.” But he realized he was hurting his loved ones. “People want you to share your feelings; they want you to talk. When you don’t, they think you are angry; they don’t understand that you are just conditioned … that you’ve been conditioned,” he said. Nelson M. underscored the stigma attached to incarceration. “People look at you as the old you. In their eyes, you are still the young kid you were when you got locked up.” As it became harder for him to convince some of his relatives that he was now a grown and mature man, he lost his desire to be around them.

Finally, access to adequate mental health resources is also difficult outside of prison. Barriers to mental health care upon release include limited access to providers, difficulties in navigating the system, lack of insurance coverage, stigma, and fear of judgment. Out of 18 participants who were formerly incarcerated, only three received mental health care inside prison, and only two were encouraged to go to therapy after coming home. All five men who received mental health care inside and/or outside prison credit it for their growth and well-being during and after incarceration.

Housing and Employment Barriers

Finding a home after incarceration can be difficult. People who are released after decades in prison can be confronted with bias from both private property owners and public housing authorities. Furthermore, they might be ineligible for public housing assistance because of their criminal records. Without appropriate support, people can be engulfed in cycles of incarceration, as homelessness increases the chances of interacting with law enforcement. Although most participants said they were lucky to have a home upon their return, some experienced significant difficulties. Jacqueline M. shared that her landlord kicked her out of her first apartment because a relative brought in a firearm. She then lived in her car for several months before securing another home with the help of her friends.

Participants in this project expressed that they struggled to find employment. Adverse childhood experiences and time spent in prison without educational opportunities had set them back. Nelson M., who served just under three decades, explained, “I didn’t know anyone who worked in the office, ever. Except for seeing it on TV, I didn’t know anyone that got up every morning to go into an office. I didn’t know no one that didn’t have to shower when they came back home from work. No, I’ve never seen that as a kid. So I never thought of it for myself.” Jermaine J., who spent 24 years behind bars, recognized how being excluded from furthering his education during the first decade of his incarceration negatively impacted his personal growth and preparation for coming home. “If I had been in a joint like [Kewanee Life Skills Re-Entry Center] or had the opportunities [earlier], I’d be in better shape.”

A few participants had the chance to develop skills through vocational training during their incarceration. After their release, however, they faced discrimination, as many employers are reluctant to hire people with criminal convictions. In fact, it is mainly as job seekers that they experienced the lingering effects of lengthy incarceration. Kevin M. said several job offers he received were canceled after the background check came in. It was frustrating and disheartening for him that no employer was ready to look beyond his conviction. “I’m trying to do better with my life; I just need someone to give me a chance,” he said.

Another significant obstacle to reentry is the scarcity of financial resources. Many interviewees were excited by the prospect of starting their own businesses upon release. Unfortunately, reality quickly caught up with them as they had no financial support to do so. With no permanent source of income, no credit history, no savings, and no one to assist them, bank loans were out of their reach. William N., who received a life sentence at the age of 17, summarized the situation: “[After prison], it’s hard to ever feel financially secure.”

Meaningful Employment

Despite challenges around employment, many people who had JLWOP sentences are thriving in their careers after spending decades behind bars. They are showing society that they are not “irredeemable.” Most of them are working full-time, hoping to drive positive social change. They are engaged in various fields of work, including restorative justice, entrepreneurship, the service industry, and nonprofit work, particularly in criminal legal reform.

- Marshan A. spent 25 years in prison. He is now the Director of Policy and Communications at the advocacy organization Illinois Prison Project. He is also in law school and, upon graduation in 2026, plans to continue to advocate for people who are still incarcerated.

- Eric A. served 27 years of his life sentence. Today, he leads restorative justice practices inside prison facilities to foster spaces where people who are incarcerated can engage in meaningful opportunities for understanding, empathy, healing, and growth.

- Jamie J. was imprisoned for 29 years. Since his release, he’s found his career path: making diesel exhaust fluid for trucks.

- Jacqueline M. was the only female to receive a mandatory life without parole sentence in Illinois. She was in prison for 31 years. Since coming home, she has been a motivational speaker and a mentor for underprivileged youth.

- Nick M. was exonerated after serving 25 years behind bars for a crime he did not commit. He is now pursuing a career in art and construction.

- Wendell R. was incarcerated for more than 25 years. After his release, he started working at Restore Justice as an apprentice. He is now the organization’s Executive Director. He also mentors youth who are at risk of incarceration.

- James S. had been in prison for 28 years when his clemency petition was approved by the governor. After graduating from Restore Justice’s Future Leaders Apprenticeship Program, he became the organization’s Policy Manager. He is proud to advocate for a more humane and compassionate legal system in Illinois.

- Steven M. was wrongfully convicted and received two natural life sentences. He spent 25 years behind bars. Since his release, he has had several jobs, including at a nonprofit organization and in the service industry.

- Michael W. served 27 years of his life sentence. Once released, he started a catering business with his wife. His goal is to thrive as an entrepreneur.

These are only a few examples of people finding meaningful career pathways to serve their communities and support their families after serving lengthy JLWOP sentences.

Community Service and Advocacy

The desire to give back to the community and advocate for people who are still incarcerated emerged as recurring themes among project participants who have returned home. Many of those interviewed felt indebted to society and the people they left behind in prison.

After years away from home, most participants wanted to reconnect with their communities by engaging in activities that would positively impact others. Interviewees expressed an interest in working with nonprofits, religious groups, and other mission-driven organizations to help their communities thrive by promoting community safety, expanding access to education, and providing economic opportunities and social support. Most interviewees reported involvement in volunteering, mentoring, advocacy, and activism. For example, Wendell R. partners with Legacy Reentry Foundation, a nonprofit organization that provides resources such as life skills training, job preparation, financial literacy, and trauma-informed care to returning citizens.

Many project participants felt moved to give back to their communities by using their stories to help children and young people, especially those at risk of incarceration. Overwhelmingly, they believed sharing their stories could positively impact those struggling at home and in school who are more vulnerable to becoming involved in the criminal legal system. Kevin M. shared his experience volunteering with a nonprofit: “We go to communities and speak to the people who are responsible for violence, in particular gun violence. We know them, and we understand them because we have been there, so we try to talk to them about education, discipline, peace, as well as the risk of being locked up for years.” Kevin M. added that helping restore pride to these communities, including his own, is a source of joy. Nick M. expressed the desire to show younger generations how new skill sets such as drawing, painting, and carpentry could change the course of their lives. “If I can teach them how to make money with their hands, they will be a gold mine because people will invest in them,” he said.

Participants who have navigated the complex reentry landscape are also eager to use their experience to support other returning citizens. Most of them expressed the desire to be a resource for people who are returning home from prison. “I think it’s imperative that we [help] more guys when they come home with the little stuff: IDs, technology, and driver’s licenses,” Nelson M. stated. “[They need] somebody that can give them a pull up before they come home, somebody to hold their hand when they come home, and somebody who kind of knows the system to help them navigate through registries and that type of stuff.” This solidarity stems from the strong bonds they formed behind bars. Interviewees repeatedly pointed out that they are part of this “brotherhood” for life. For example, Michael W. declared: “My incarceration made me the man I am because I met these brothers. It made me stronger mentally and physically. Spiritually, I can only give that to God, but God put each and every one of those individuals in my life for a reason.”

Project participants also acknowledged that many other people who are still incarcerated deserve a chance to demonstrate their growth and rehabilitation. Those who are home see themselves not as exceptional cases of what is possible for people who have served lengthy sentences, but as examples of the good many others can do. “I never understood the phrase ‘survivor’s guilt’ until now,” Nelson M. said. “I have guys that call me regularly that have the kind of [prison] time I had, same cases, and the only thing different is they were born two months too late [to be Miller-eligible]. You feel guilty for being here, so you just really want to do your best.” Jamie J. voiced similar eagerness to inspire those still incarcerated, whether or not they have an out date. “I want to be an inspiration to the guys who are trying to get released. I want them to see my progress and believe that living a productive life after prison is possible. It may take some time, but I want to make a ray of light for them,” he said. Marshan A., who provided legal support to many people while he was incarcerated, is determined to continue to help those still confined behind prison walls. “I had no desire to be a lawyer until I got incarcerated and started learning the law and realizing the need for those things I carry with me forever,” he explained.

Aspiration to Freedom

While some people still serving juvenile life without parole sentences in Illinois have out dates, others do not. Notwithstanding their circumstances, all respondents expressed a strong desire to regain their freedom and have the opportunity to contribute meaningfully to society.

Those with release dates eagerly anticipate the day they will walk out of prison as free men. They shared plans to rebuild familial relationships, meet professional goals, and reach financial stability. Decades of incarceration have deprived them of important moments with family and friends: school dances, birthday parties, graduations, and weddings, among others. After missing so many milestones with their loved ones, they look forward to making up for lost time. Joyce H., who has been imprisoned for three decades, said he is patiently waiting for the day he will be set free. Having up to seven more years behind bars does not curb his enthusiasm. “My dream is to get out and make my life count for something. I want the world to know that I’m ready to show up and do what I need to do to prove I’m deserving of a second chance,” he said. Like Joyce, Adam D. still has approximately seven years left on his sentence, but he has goals in mind for the future. Having already authored some coloring books, he described his yearning for new beginnings. “My dream is to get out healthy enough to publish more books, shoot some movies, sell some food and clothes.”

Interviewees with no out date also expressed faith and hope for changes in the law to help them return to the community. For Dwight P., such legislation would signify a positive change in societal attitudes toward crime. It would reflect lawmakers’ better understanding of neuroscience that shows that the brain continues to develop well into a person’s twenties, and that children cannot be held to the same standards of responsibility as adults. The U.S. Supreme Court has consistently emphasized that children are uniquely capable of transformation, particularly in its rulings that prohibit sentencing children under 18 to death or mandatory life sentences. However, state laws have been slower to fully recognize and reflect this understanding, continuing to treat children as adults in some legal contexts.

All project participants who are currently incarcerated articulated their willingness to take full advantage of the miracle of freedom if they are given the opportunity. Yank C., who has been in prison for 14 years, mentioned that his dream is to make good memories that can outweigh the trauma of childhood. At age 30, he has spent most of his formative years behind bars and aspires to enjoy life. “If I could have a sentence that could get me home at a reasonable age, it could mean everything. I don’t have kids, and I don’t have any fun memories of life. I would like to experience life, love, and fatherhood,” he shared.

Loved Ones

Sentencing a child to die in prison has a ripple effect on communities. Removing young people from their homes and families harms parents, siblings, relatives, partners, and friends. Family members interviewed for this project emphasized the significant financial, emotional, and social impact of JLWOP sentences.

A child’s arrest, pretrial detention, and trial(s) are emotionally draining for family members. Though parents and other loved ones are not on trial, they are often blamed and shamed throughout the court proceedings. Getty M., whose son Steven M. was wrongfully convicted and given two natural life sentences, described their years in court as “a battle.” She was particularly distraught by the way her family was humiliated during the trial. “The prosecutor hated us. They described us as people who were so superficial, who didn’t have feelings for the victims’ family. They spoke about our kids as if they were just running loose. They painted a picture that was so far from the truth. We were called names by people who didn’t even know us. Not once did anyone talk to us or ask questions about who we were or how we felt,” she recalled. For Getty M., just like for other mothers interviewed, the pain and suffering associated with the trial became excruciating when her child received a natural life sentence. Marshan A.’s mom, Leah, recalled how crushing the verdict was: “I cried and felt like I was going to faint because I didn’t think he would get that kind of sentence. I was very emotional. Everybody in the family was crying. We were shocked.”

After the emotional stress of a loved one’s trial and sentencing, people providing support from the outside then have that stress compounded by the repeated difficulty of only being able to visit them in prison. Visiting loved ones in prison can be emotionally challenging because of the rules that vary from facility to facility, the unpredictable behavior of prison staff, and unforeseen circumstances that can limit visitation. Visits can be canceled with very limited notice if a facility is suddenly placed on lockdown. In these cases, it does not matter how long in advance a visit was planned or how far the visitors have traveled – the visit is simply canceled. Visitors are also searched when they enter a facility, and those searches can be humiliating when performed inappropriately. There are many rules about what visitors are allowed to wear, and those rules can be unevenly and arbitrarily enforced by staff. Visitors are often nervous about saying or doing something wrong, because the prison staff can ban them from visiting their loved ones in the future. Nicole S., who visited her brother several times, talked about the trauma of visiting the prison. “I was always scared to go to the buildings. I didn’t like how I was treated, how we were treated, coming inside the buildings. We felt like we were the offenders as well, coming in, having to be searched; the way they talked to us, the way they just treated us. I felt like everything was inhumane,” she said.

In addition to the emotional stress of having a loved one who is incarcerated, there is a significant financial burden. Family members who were interviewed for this project all underscored the financial challenges they experienced as they tried to support their incarcerated loved ones and maintain relationships with them. Families noted that, even when a person who is incarcerated has a job, the pay is extremely low. In Illinois, people who are incarcerated earn between $0.09 and $0.89 per hour for non-industry jobs and between $0.30 and $2.25 per hour for industry jobs.27 Because of these extremely low wages, people who hold jobs in prison often still need monetary assistance to purchase books, basic hygiene supplies, and items from the commissary to supplement their diet. “What they make [in prison] is a couple of dollars a day or something. And the food is pretty inadequate. And they need other things, clothing that they can buy from there, and toiletries,” said Julie A., whose son spent almost three decades in prison.

It is also expensive to visit a loved one in prison.28

The remote locations of the majority of Illinois prisons impose long and expensive trips on families. In visiting rooms, the only option for sharing a meal with a loved one who is incarcerated is to purchase packaged snacks from vending machines at an exorbitant markup. Julie A. noted how economically taxing it was to stay in touch with her son, especially during his stay at Menard Correctional Center, located almost six hours away from her home in Chicago. “It was super expensive! We drove down there a lot of times, visited, stayed overnight, visited the next day, and then drove home. So, we had to pay for gas, hotel stay, and eating out, plus we also spent money in the visiting room to eat, which was super expensive.” The financial burden was so heavy for some families that they had to interrupt prison visits for a while. Lydia H. recounted that there were times she could not see her nephew or send him money because she was struggling financially.

Despite their young age, a number of the people who were sentenced to JLWOP in Illinois were parents before they were arrested, meaning that they also left behind children. Children of incarcerated parents are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and physical health problems. The trauma associated with having a parent incarcerated can lead to lower educational attainment and developmental-behavioral concerns. Children of incarcerated parents are also more likely to be involved in the criminal legal system in the future.29 Children are particularly vulnerable to anxiety related to parental imprisonment. It can be difficult to handle the absence of a parent and the lack of guidance, comfort, and stability it generates. Cwon T., whose father was imprisoned before he ever had a chance to meet him, recounted his pain growing up without a father figure. “I didn’t have anyone to talk to about the things that I was experiencing in school, from just wanting to be a kid, to having my dad at my basketball games,” he recalled.

Relatives of all ages who participated in this project identified social stigma and rejection as another common effect of imprisonment on families. “Some of our family members were very judgmental of us, of the whole situation. So, my mother looked depressed. She didn’t have a lot of people behind her, supporting her, and it was very sad,” Nicole S. commented. Lydia H. noted that most of their relatives “vanished” during her nephew’s long ordeal with the criminal legal system. And if her sister’s agony over her son’s incarceration was heartbreaking, the stigma and abandonment from other family members she also had to face were crushing.

The negative effects of incarceration on families continue even beyond the time served. Families experience joy at having their loved ones return home and challenges adjusting to their presence after a lengthy absence. The so-called “juvenile lifers” involved in this project were arrested as children and released as middle-aged adults, having missed both important family milestones and also dramatic changes in the world outside. Now, their families have to help them catch up. Getty M. shares that she and her family “are still trying to help Steven M. advance 30 years.” Cellphones were not widely used when most project participants started serving their sentences, and the internet was in its infancy. Catching up with technological advances and navigating housing, jobs, and relationships can be overwhelming. Families and friends work hard to find the best ways to support their loved ones throughout reentry.

Families are rightly called the “hidden victims” of the criminal legal system.30

Like their loved ones in prison, they need support to handle the financial, emotional, and social burdens associated with incarceration.

Looking Ahead

While some people sentenced as children have received relief from Supreme Court rulings, many have been excluded. Miller ruled narrowly that only mandatory life sentences are unconstitutional for children who were under 18 at the time of the crime.31

As a result, judges can still give discretionary life without parole sentences to children under 18, provided that the child’s youthfulness and other mitigating factors (also called “Miller factors”) are taken into account.

The U.S. is the only known country in the world that permits JLWOP sentences, making many states a global outlier. Just over half the states in the U.S., including Illinois, have abolished JLWOP32 by enacting youthful parole opportunities and outlawing the practice of sentencing children under 18 to life without parole.33

The Miller decision and the abolition of JLWOP have not completely eliminated such sentences from the Illinois criminal legal system. Many people who were given mandatory JLWOP sentences in Illinois between 1979 and 2012 have been resentenced to discretionary life sentences. Although the Illinois Youthful Parole bills passed in 201934 and 202335 ensure that most people under 21 are eligible for parole consideration, they only apply prospectively. This means that they do not apply retroactively to people who were sentenced before 2019 when these laws went into effect. However, most states that have abolished JLWOP made the changes both retroactive and prospective.

Many young people were sentenced under similar circumstances and with similar outcomes but may not qualify for relief under the narrow definition of Miller. Hence, prison sentences of four or five decades or more are effectively life sentences, but there is not a magical point of maturity when a person turns 18. Youth in their late teens and early twenties also deserve special consideration. Young adults aged 18-25 are vulnerable to peer pressure and risky behaviors, just as their younger teenage counterparts are. Scientific studies have repeatedly concluded that the brain does not fully develop until the mid-20s, and people whose brains are still developing are especially capable of growth and change as they get older and mature. Studies of this population’s exceedingly low recidivism rate produced further evidence that the population overwhelmingly “ages out” of crime.36 Increasingly, court decisions at both the state and national levels, such as the Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling in People v. Buffer (2018), are beginning to recognize the urgency of addressing de facto life sentences of 40 years or longer and the special characteristics of young adults.

Conclusion

No one should be defined only by a conviction or their worst mistake. Children and young people should not receive extreme sentences that do not account for their unique capacity to mature and change.

Excessively long stays in Illinois’ prisons are the result of punitive sentencing laws and harsh criminal statutes enacted over the last decades, which have dramatically increased the prison population. These policies removed opportunities for people to earn time off their sentences and demonstrate rehabilitation during sentence review. As a result, people who express remorse and a sincere desire to give back to their communities and families may continue to serve excessive sentences even when it no longer serves the interest of justice.

Lengthy incarceration is highly detrimental to physical and mental health and has long-term effects even after a person returns home. It also destabilizes people’s lives, disrupts family dynamics, and harms communities. Long-term incarceration deprives communities and families of the unique contributions people serving extreme sentences can make and penalizes their loved ones who serve time with them. After spending decades in prison, people who are released can contribute immensely to the community, promote well-being and healing, and prevent future harm.

Sentencing children and young people to life in prison is unacceptable and wrong. Adolescents are capable of rehabilitation and should be held accountable in age-appropriate ways with a focus on rehabilitation and returning to the community. Policy changes are urgently needed to reflect the evolving standards of decency: people are more than their convictions.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

This project underscores the necessity of continuing to enact legislative and administrative reforms to allow those who are rehabilitated to go home and ensure those incarcerated, their loved ones, and victim families have opportunities for healing and justice. Illinois needs to adopt a rehabilitative rather than punitive response to children engaging in criminal behavior that recognizes children’s potential for positive change and growth.

Reform Sentencing and Create More Pathways to Release

- Ensure fairness and consistency by applying all sentencing reforms and pathways for release both retroactively and prospectively.

- Expand youthful parole opportunities to people 25 or younger at the time of the crime for which they were convicted. Apply existing youthful parole legislation retroactively to people in Illinois who were sentenced before the state’s Youthful Parole Act was enacted in 2019.

- Continue sentencing reform, including abolishing life and de-facto life without parole sentences.

- Increase opportunities for proactively earning sentencing credit through good behavior and participation in rehabilitative programming.

- Eliminate mandatory sentences and mandatory firearm enhancements so judges can use discretion when considering youthful characteristics and other mitigating factors and in deciding individualized sentencing for each case.

- Limit the use of accountability theory and felony murder so people are not convicted of crimes they did not commit or intend to commit.

- Provide meaningful pathways for release, such as automatic judicial resentencing, expanded parole opportunities, and increased use of executive clemency, pardon, and medical and compassionate release.

Provide Reentry Support During Incarceration

- Ensure people sentenced to life or de facto life sentences have access to education, vocational and life-skills training, and trauma-informed health care, including robust mental health care.