When state legislatures across the nation began abolishing parole in the late 1970s, their rationale was often that parole failed to increase public safety or reduce repeat offenses. They pointed to old data plus a few isolated cases of people on parole committing new serious crimes.

However, more up-to-date research shows discretionary parole can effectively reduce the likelihood of new crimes. The Pew Charitable Trusts found that people on parole in New Jersey were 36 percent less likely to commit new crimes and return to prison compared to “maxouts,” or people released at the end of their terms and without parole supervision. Separately, a 2005 study by the Urban Institute compared the benefits of discretionary parole to both unconditional releases and mandatory parole. The authors of the Urban study found that, in some cases, parole could reduce the predicted likelihood of a person’s rearrest by a significant amount, compared to unconditional release.

Technical violations, not new crimes, drive most of parole rearrests

Some studies suggest parole does not effectively reduce recidivism. These studies point to the comparable rates of recidivism between people on parole and people released without supervision at the end of their prison terms. But recidivism definitions are inconsistent. Some sources of data fail to differentiate technical violations from new crimes, rearrests from returns to prison, or new felony convictions from new misdemeanor convictions.

Only people on parole and other individuals under parole-like supervision may be arrested and returned to prison for technical violations. This can include missing an appointment with a parole officer, alcohol consumption, or failing to find a suitable home.

When data sources distinguish between technical violations and other offenses, the benefits of parole become clearer. For instance, in their 2015 report, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reported that while 34 percent of the more than 24,300 people in Illinois exiting mandatory supervised release (MSR) or parole returned to prison, only 1 in 5 of these people were re-imprisoned for new crimes. That means that for all individuals in Illinois exiting parole-like supervision in 2015, only about 7 percent were reincarcerated for new offenses.

These data are especially noteworthy when one considers that the majority of people on “parole” in Illinois are on MSR and not parole. This means that most of these released individuals were not granted release based on a careful assessment of their likelihood to reoffend.

People convicted of violent offenses are less likely to reoffend

Many express concern that granting parole to people convicted of violent offenses means that — should they offend — these individuals will inevitably commit new violent crimes. But the data tells another story.

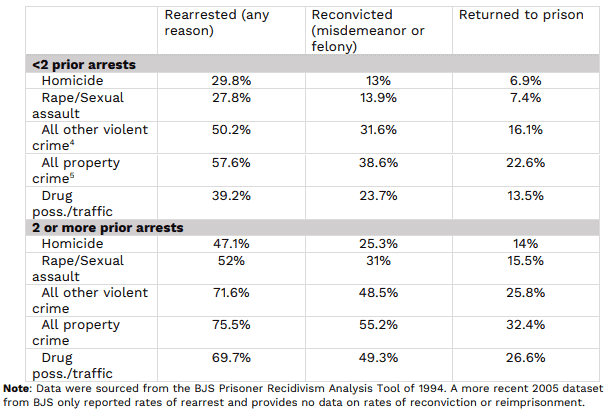

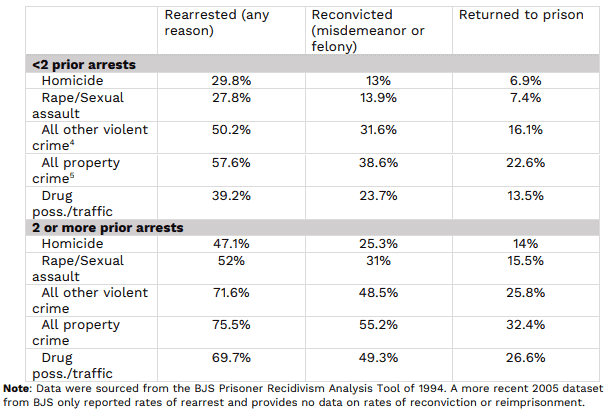

Table 1. Rates of rearrest, reconviction and returns to prison with new sentence within three years, stratified by number of prior arrests and offense type

These data suggest that:

- Regardless of the number of prior arrests, people convicted of violent crimes are less likely to return to prison for a new sentence than those convicted of property crimes.

- People convicted of murder are least likely to return to prison with new convictions, especially if they had few prior arrests.

- Regardless of offense type, people with fewer prior arrests are less likely to recidivate compared to those with more prior arrests.

What about the relationship between a person’s original offense and subsequent ones? When they do commit new crimes, are people previously convicted of violent offenses more likely to commit new violent felonies upon release?

A study on from BJS sought to answer this question by examining the correlation between a person’s original committing offense and arrests for subsequent, post-release offenses.

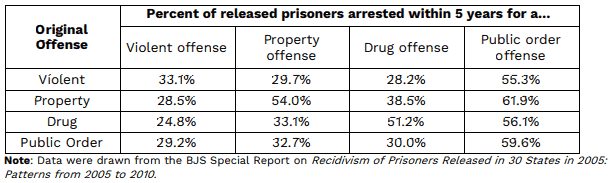

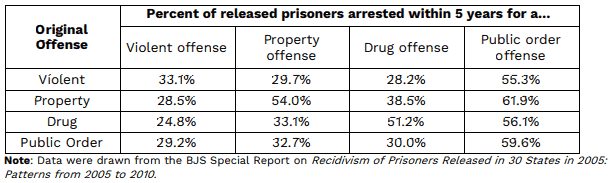

Table 2. Rate at which people are rearrested within five years for certain types of offense, based on type of original committing offense

Recall that rearrests do not automatically equate to new convictions or prison terms (as evidenced in Table 1).

No matter what an individual’s original offense, the BJS found that the most serious offense for over half of all rearrested individuals were for public order offenses, which include disorderly conduct, loitering, and similar crimes.

And while those convicted of violent crimes were more like than other individuals to be rearrested for a violent offense, they are also less likely than individuals convicted of property crimes from reoffending in the first place.

Parole supervision costs less than incarceration

According to a 2015 spokesperson from the Illinois Department of Corrections, it costs Illinois roughly $22,000 to house an incarcerated person for one year, compared to the $2,000 it costs annually to place that person on parole. This lines up with national data from a Pew study that put the cost of placing a person behind bars for a single day is on par with 10 days of parole supervision.