Eric Anderson

The trajectory of Eric Anderson’s life completely changed when he was sentenced to die in prison for a crime he committed at age 15. Now released after almost three decades in prison, Eric is an advocate and a restorative justice practitioner who uses his voice and story to transform people, systems, and communities.

“Responsibility involves doing the best you can to repair the harm that you have caused in life.” – Eric Anderson

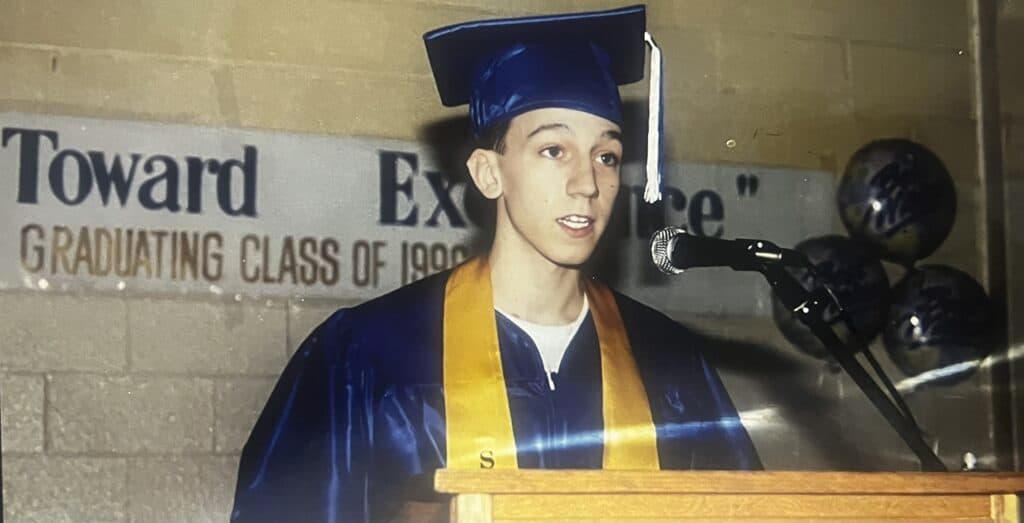

Eric Anderson was a 17-year-old boy when he was sentenced to life without parole for murder and went to state prison. Since his release after more than 27 years in prison, Eric has become a strong advocate of criminal justice reform. He is also using restorative justice practices to bring comfort and change to some of the correctional facilities where he spent several years of his life. “Restorative justice practices are a way to give back, as I can get those I was incarcerated with involved,” Eric says. “I mostly engage in peace circles because I intrinsically feel the power of the ability to share with people in a safe space. It’s really powerful; it’s really cathartic.”

A Boy Trying to Fit in

Eric describes his childhood in Garfield Ridge, a southwestern, working-class neighborhood of Chicago as “pretty decent.” “I lived with my parents and siblings,” he says. “My dad was a police officer, and my mom was a real estate agent. I had a regular upbringing. We did not have a lot of extra money around, but we had a nice house, and we went on vacation every summer.” He remembers being enrolled at a Catholic elementary school, and later, a Catholic high school.

Eric also remembers his desire to fit in with those he perceived as cool kids. “I strove to fit in. As I got older, I started hanging out with kids who were headed down the ‘wrong path’ as people would say. We were all just making what were ultimately unhealthy life choices. We did what kids do.” He adds, “I was an example of getting in trouble because I perceived that my peers thought it was cool. I thought that raised my esteem with them.”

As a result of wanting to fit in, Eric joined a gang when he was about 14, lost interest in school, and was eventually expelled. “When I was expelled from the Catholic school that I was attending, I couldn’t even start at the public high school close to my house because of gang issues. I was getting into all kinds of trouble, and engaging in criminal activity with older teenagers in order to earn my place in their eyes,” he says.

Eric now understands how his interaction with gangs led to a chaotic, uncontrollable life. “It was a very turbulent time for me. I had quasi/officially dropped out of high school after completing about two months of my freshman year, and I had gone to some outpatient mental health services on a regular basis as a substitute for school for maybe a month or two. When that failed to produce any tangible benefits on my behavior, my family sent me to a boarding school in Kansas,” he says. But this was a short experience, as Eric was expelled and sent back home. From then on, things continued to spiral out of control until he was finally arrested and charged with murder.

“We are Family”

For the most part, Eric’s recollection of his arrest and short stay at the police station is blurry. But he recalls being in a “super special situation,” as his father was a Chicago police officer. Unlike other parents whose children have been arrested, “My dad was given the privilege to interact with me at the police station. He was allowed to be there for me,” he explains.

His father’s words during their first encounter provided much-needed comfort. “My dad turned to me, and he said ‘Look, man, whatever else happens, whatever did happen or will happen, we are family. Just know that, and don’t ever question that.’” This powerful expression of love became engraved in Eric’s mind, becoming his source of strength. “That was the thing that carried me through a lot of years and still does,” he remarks.

These words were quite reassuring throughout the legal process, especially as the case drew a lot of attention. “My co-defendants and I were not your clichéd stereotype on the 6 o’clock news. This was bad! This was cops’ kids in a white neighborhood, with white victims of gang violence,” Eric recounts. “It seems that the prosecutor had his personal intrinsic motivations. He wanted to really make this the most sensational thing that could advance his career. And today, he is under strict scrutiny for all the decisions he made back then, including coercing my co-defendants to lie.”

At the end of a lengthy trial, Eric was convicted and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole, a concept he was not familiar with. He explains that neither he nor his co-defendant realized how this judgment was going to alter their lives. “We were outside the courtroom with about 15 to 20 other people, and we were joking. When people asked us why we were in court, we were just like, ‘We are getting sentenced today.’ And when they asked how much time they were going to give us, we were like ‘natural life without parole.’ We did not understand what was happening. Literally, we might as well be talking about a new episode of ‘Cheers’ coming on that night,” he remarks.

Life in Prison

After spending months at Cook County’s Juvenile Detention Center, popularly known as the Audy Home, Eric was transferred to the Cook County Jail when he turned 17. He was held with adults and tried in adult criminal court. Eric started serving his post-conviction sentence in Joliet Correctional Center. At the time, it was known for being the least aggressive of the four maximum security prisons in Illinois. “Joliet was mostly for people the Department of Corrections considered vulnerable: smaller stature, younger ages, white kids. I fit all three of those categories at the time. I was 18, I didn’t have any facial hair, and I looked like a little kid. So they took me to Joliet,” he says.

However, less than two weeks after his arrival, Eric was involved in a riot and transferred to Pontiac Correctional Center, which was a “major segregation and protective custody prison.” After 6 months in solitary confinement, he was transferred to Stateville Correctional Center, another maximum security prison. Looking back, he notes that his “roughly 5-year experience in one of the highest aggression maximum-security prisons in the state was pretty terrible,” mostly because he spent the majority of that time in “solitude and disciplinary segregation” for various reasons, including gang affiliation.

After Stateville, Eric was sent to Menard Correctional Center, where he spent the majority of his time behind bars. In retrospect, he believes his transfer to the state’s largest maximum-security facility was a positive change. “Menard definitely changed the trajectory of what was happening to me,” he reflects. “I was in the throes of unhealthy decisions, and I was purposefully engaging in things that were definitely going to be detrimental to my health. But when I got to Menard, at age 23, my attitude changed. I started doing a lot of reading, a lot for self-analysis,” he recounts.

Eric reveals he started asking himself some important questions that helped him: “What are you doing every day, why are you making these choices? What is the motivation? And what are you trying to do?” Answers to these questions did not come easily. Eric says his thought process was guided by one principle. “If you know where you are trying to go, and you can know where you’re at, then you can have a path to where you’re trying to go.” As he internalized this idea, he matured and came to grips with a lot of the harms he had caused and was continuing to cause by “being alive and incarcerated.”

Finding a Purpose

Eric’s self-awareness significantly improved as he thought about the weight of his incarceration on the people who had been assisting him since his arrest. He thought about his dad working as a police officer. “I thought about how it affected him personally at his job. That’s the thing that crushed me. I couldn’t imagine what that was for him to go to that job,” he laments.

This made him more appreciative of the social support he had been receiving since the beginning of his case. “My whole family was invested in this. I am well adjusted as an adult because of their constant phone calls, letters, pictures, interactions at every level,” he observes. In addition to encouragement and comfort, his family ensured that he had legal representation throughout his incarceration. Eric is particularly grateful to his mom for being the pillar of this support system. “My mom is an amazingly organized person. She is one of the most capable humans I’ve ever met. She can literally bring something out of nothing. She made things happen for me,” he says.

Eric also thought about the cost of imprisonment, and the financial hardship his family had to endure. “I spent some time in a medium joint. I spent some time in a very minimum-security joint. But most of my life was in a maximum-security penitentiary, and financial support in such an institution is a serious thing,” he explains. “It’s a burden for people. It’s a complete burden for people who love and support you.” Eric explains that maximum-security prisons like Menard are located in more remote areas than minimum and medium-security ones are. This increases the cost of visits, given that loved ones often have to spend the night in a nearby hotel. Moreover, those who are incarcerated in maximum-security facilities have fewer work opportunities, and thus need financial assistance to purchase basic necessities, which are usually sold at steep prices in the prison store, or commissary.

Eric emphasizes that in prison, people are tempted to engage in really dangerous interactions and behaviors because of the lack of money. “In prison, the situation is very precarious, and it’s even worse when someone is not financially stable.”

Eric’s reflections also led him to the realization that he would spend the rest of his life behind bars. “I became keenly aware of the fact that I had an actual life sentence. I was 26 or 27 years old then, and I was like ‘That’s it! I’m done with my appeals! It’s over now! All is lost, I’m never going to get back to court’,” he remembers. “It was like a doctor coming to me and saying, ‘You have Stage 4 cancer and you have a limited amount of time to live.’”

Having come to terms with his sentence, he decided to make his incarceration “as sweet as possible” by avoiding confrontation and following rules. “I was the luckiest person ever. I stopped catching tickets. I started working in the maintenance department and became an electrician. And that’s one of the things I did right.”

By the time the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that it was unconstitutional to sentence children to die in prison, Eric had already spent almost two decades in prison. He remembers having mixed feelings about the ruling. “I was excited. I thought, ‘the decision might as well literally say Eric Anderson, you are going back to court for a resentencing hearing,’” he says. “But having been through the Illinois legal system and having watched other people go through it for many years, I was very hesitant to think that the decision would result in my release. There’s no way I could have contemplated that at that time; that was beyond the realm of what was feasible,” he adds.

Eventually, Eric was resentenced pursuant to Miller and several other state decisions, including People v. Davis, which made Miller retroactive in Illinois. His new sentence of 60 years was to be served at 50 percent, under the statutory good times table. Finally, in April of 2023, after almost three decades in prison, Eric was released.

The Scars of Lengthy Incarceration

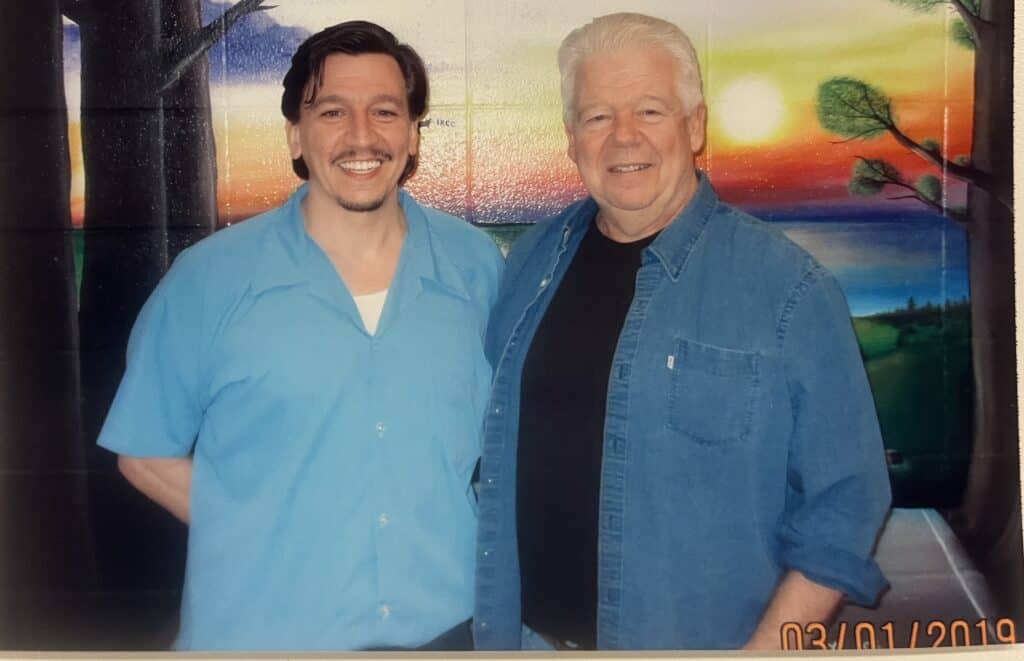

When Eric walked out of prison, he was warmly welcomed by his loved ones. The “emotional proximity” he felt throughout his incarceration was now strengthened by physical proximity. “My family is tied for the people who are closest to me,” he says. On the other side of this tie are his best friends Mike and Nick, who were incarcerated with him. “We went through a lot together, in and outside of that cell. Prison can shatter people and relationships. We weathered the storm. These two are like my family,” he states.

But Eric did not walk out of prison without scars. “A lot of traumatic things happened to me; there’s a lot of damage that I try to cope with on a regular basis,” he asserts. For example, he “hates making a doctor’s appointment because the process is a pain,” and reminds him of prison. “Going to the healthcare unit in a maximum security prison was a supreme pain. The six layers you had to go through to see an actual doctor was such an insane pain that people didn’t want to do it,” he remarks. In addition, the medical unit was incredibly small, and thus provided incarcerated people with “the opportunity to settle their scores,” resulting in violence.

Being incarcerated at a young age negatively impacted Eric’s behavior. “What happens in prison is unacceptable,” he says. He recalls being bullied, until he became very confrontational in order to preserve his safety. “I was usually the youngest in the crowd, and was generally, in all kinds of circumstances, the person to be bullied or picked on by somebody. I was always an easy target,” he explains. Violence was so prevalent that Eric thought his life would be very short. “I thought it would be shocking if I made it to 21. And I was certain I was going to die before turning 22,” he asserts. Eric became aggressive in order to survive. “While the juvenile detention center was a violent place with very little reprieve or respite, it initiated me to prison life in a way that enabled me to survive later on,” he recounts.

Eric believes the self-defense mechanism he developed in prison can account for his confrontational reactions. “I take almost everything people say to me as a direct challenge,” he declares. “The traumas I went through did a lot more damage to me in my ability to relate to people than I ever really could have understood if I had just stayed incarcerated,” he continues. Eric acknowledges that building relationships outside prison significantly differs from interactions inside prison walls: while sharing private information in prison is barely tolerated, outside, it is expected. “When people see me they think they know me because they’ve heard my story. But they don’t. All I want to tell them is to stay out of my personal life, because I grew up in prison, and prying into people’s personal affairs was very dangerous,” Eric says.

Years of imprisonment have also generated feelings of fear. Although he tries to hide it, Eric says he is often on edge, and panics easily, especially when he thinks he is at risk of violating his Mandatory Supervised Release. “I can’t describe how much and how often I panic. I definitely pat myself on the back on my ability to conceal it most of the time,” he says. Eric recalls being in a state of extreme agitation one day, when he realized he had forgotten his driver’s license at home. And although his friends assured him there wouldn’t be any issue, he exercised due diligence and used public transportation to retrieve his license from his house before picking up his car.

“Hurt People Hurt People; Healed People Heal People”

Since his release, Eric’s mantra is “Hurt people hurt people. Healed people heal people.” In order to make up for the harm he caused, he wants to give back as much as possible. In prison, he had limited opportunities to do good in a meaningful way. Now he marvels at the options available, and what he has accomplished in just a few months. “I’m moving at full speed every minute of the day. It’s very difficult for me to slow down,” he says.

Eric is particularly proud of the in-prison peace circle trainings he has been co-facilitating with Sister Janet Ryan from Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation. Returning to some of the correctional facilities where he grew up to lead circle keeper trainings is one of the highlights of his reentry journey. “In prison, I felt like I had no opportunity to make a tangible impact in any kind of way. With restorative justice practices, I have a purpose. Being able to give back to the guys who are still incarcerated means so much to me,” he declares.

As an apprentice at Restore Justice, Eric has also been advocating for criminal legal system reform in Springfield. “My first time going to Springfield as an adult to deal with legislators and lobby for legal reform was on the 6-month anniversary of my release from prison,” he recounts. Since then, he has testified several times to help advance legislation for a more compassionate justice system, including for a bill that would limit use of solitary confinement.

Eric has also been active in Restore Justice’s Returning Citizens Network, which helps formerly incarcerated people reacclimate into society. These are the people he feels “the most comfortable with,” and he believes it is his duty to participate in building a community where they can all thrive.

Eric is working hard to remain as productive as possible, and to improve his life and the lives of others. He never shies away from his past mistakes. He is keen to admit that he made unhealthy decisions, and wants to show that he has matured. For Eric, “responsibility involves doing the best you can to repair the harm that you’ve caused in life.”

More from the “More than a Conviction” Project

Up Next

Read the story of another returning citizen who was sentenced to juvenile life without parole and is now free

Read moreOther Stories

Discover the impacts of juvenile life without parole sentences in Illinois from additional perspectives

Learn moreReport

Read the Restore Justice report on juvenile life without parole and extreme sentencing in Illinois

Read the report