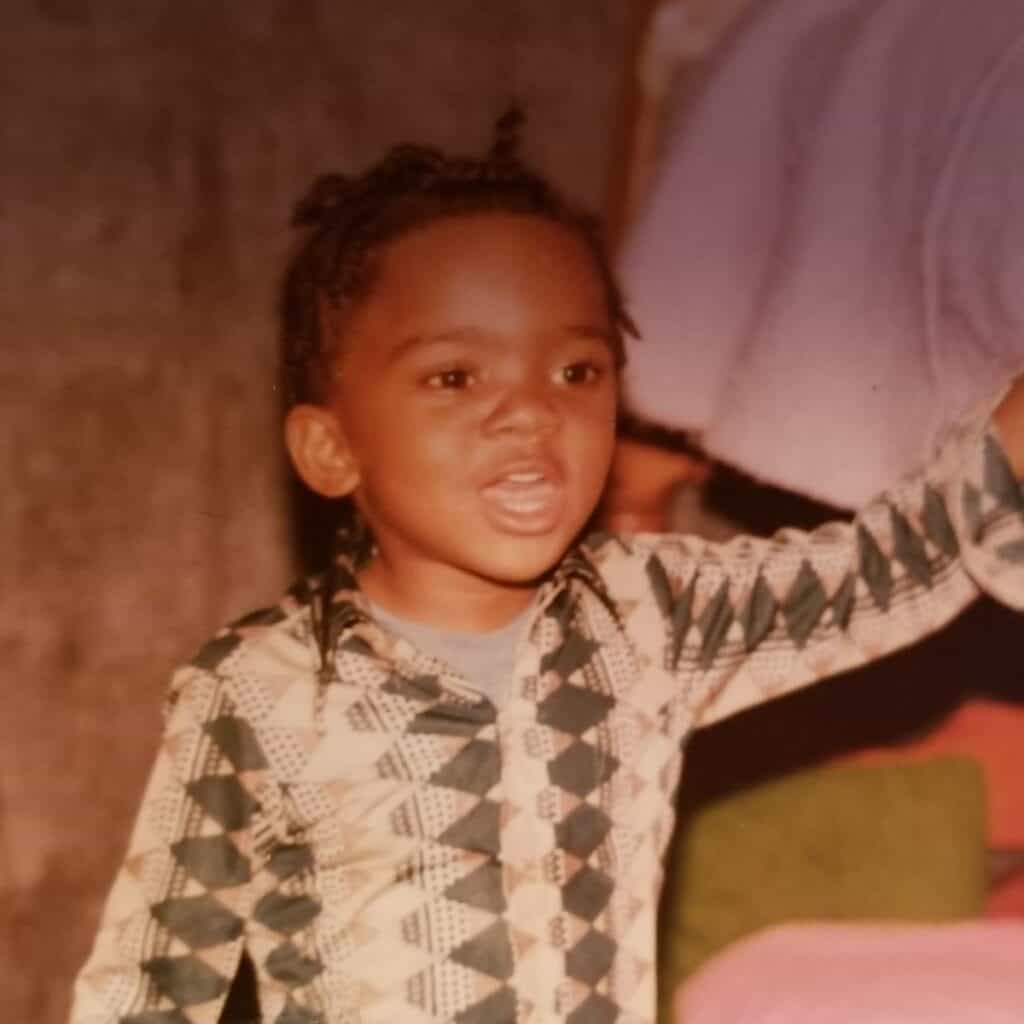

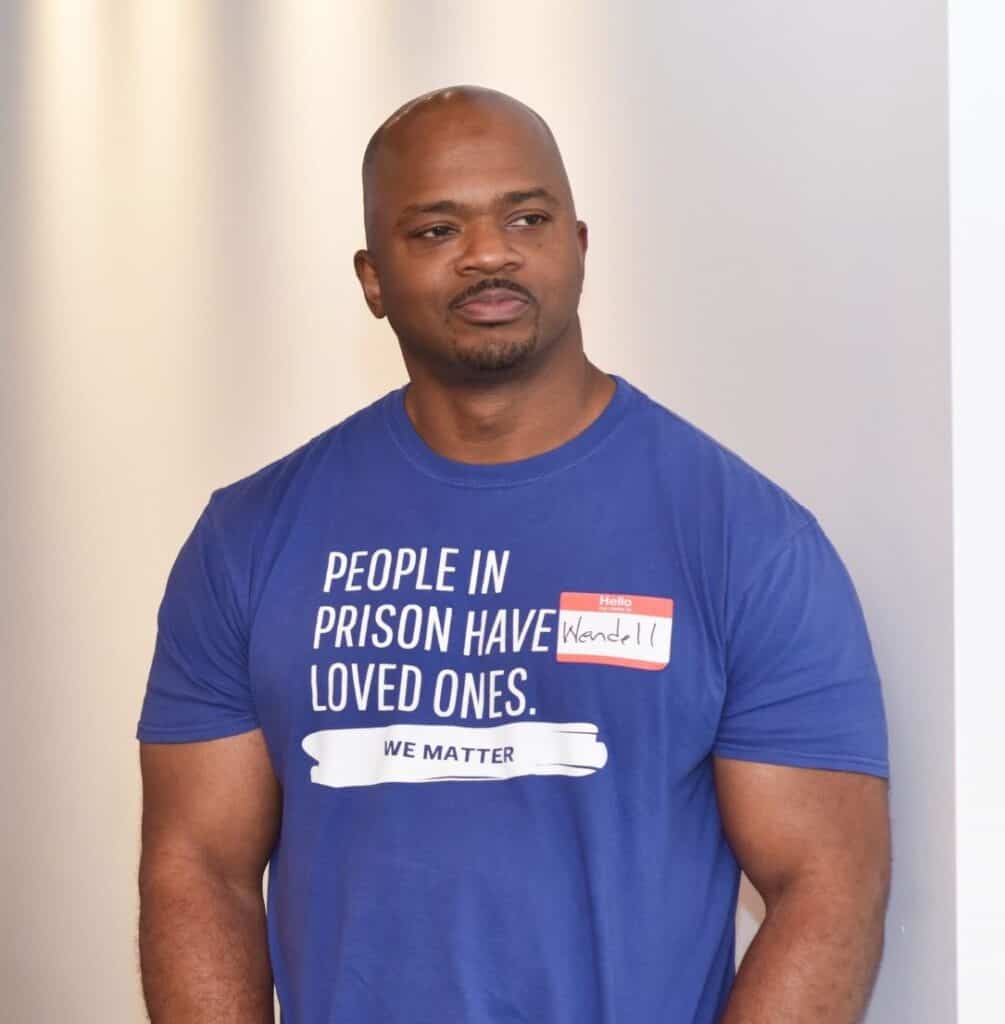

Wendell Robinson

Wendell was sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of one crime under accountability theory and another for which he maintains his innocence. He was released after spending more than 25 years behind bars and is now a leader in the fight for criminal legal reform for young people.

“A lot of children got locked away, but they were still dreaming. Every exercise they did, every book they read, was with the intention of getting here and showing the world something different.” – Wendell Robinson

Looking back, Wendell understands how his childhood came to look the way that it did: trauma, money, and drugs all impacted him and his family in different ways. After being in prison for more than two decades, Wendell started as an Apprentice at Restore Justice. Five years later, he now leads the organization as Executive Director. “When you’ve been deprived of certain stuff for so long, it’s the little things that matter so much. [Like] being able to just live a simple, productive life, on a career path that allows me to help people, like really help,” Wendell says. “The help that I give people, that’s really rewarding for me, too: to know what it’s like [to be incarcerated], and then to be the person that’s able to help.”

“Life Is Going to Be Hard”

Wendell remembers racing his young mom on the way to child care every morning when he was three years old. The route consisted of two paths: one was across a yard and around a gate, the other toward an alley and along a fence. “My head start was me getting the opportunity to shoot across the crosswalk, and she had to run all the way down … I was trying my best with my littlest legs, trying to beat my momma,” he laughs. Wendell remembers these times fondly. But he also sees their deeper meaning. “She never let me beat her,” he recalls. “She was instilling in me then that ain’t nobody going to give you nothing in life; life is going to be hard.”

And life was hard. Wendell’s first experience with death was at five years old. “I was holding my mother’s hand getting off the bus, and saw somebody get killed,” he recollects. He now understands the impact this event had on his mom, knowing what he does about trauma. “I knew that my mother didn’t like going to that store [after that]. But that’s all I knew,” he explains. “She was traumatized from that event then, but we didn’t know what it was.”

While his mother had found success in computer sales, she began to struggle with substance use and addiction by the time that Wendell was seven or eight years old. As he explains, North Lawndale, the neighborhood he grew up in, was an epicenter of the powder cocaine and crack cocaine eras of the 1980s and 1990s. “There’s this climate that was going on in the early ‘80s. And my mom kind of fell victim,” he says.

During this period, the drug epidemic reached into the lives of Wendell’s family. “One of my uncles was selling cocaine and had all of his brothers working for him,” he says. “He had me, at nine and 10 years old, helping them out with their drug trade.” Wendell’s first ever job was folding tiny envelopes, or pony packs, that held small amounts of drugs for sale.

The financial success of people who sold drugs was obvious to young Wendell. “The people that was really standing out to me in my neighborhood was the people that weren’t abiding by the law,” he explains. “I still had my grandparents, so they provided for me things that I may have needed. But at the same time … I grew up in Chicago in the Jordan era, right? I like Jordans. I want to be fresh, I want to be crispy, I want to go to school fly,” he says.

Wendell was 17 years old in the summer of 1992 when some of his belongings went missing. After he told the older man he worked for who he thought had stolen them, the accused person was killed. “I didn’t shoot anyone; I didn’t even have a gun,” Wendell attests. “But I did point that man out, and he lost his life.” Under accountability theory, a legal mechanism that holds people criminally responsible for the actions of others, Wendell was charged with first-degree murder.

Wrestling with Accountability Theory and Innocence

Months after his arrest, while he was in court for a bond reduction, Wendell was dealt another blow. He discovered during the hearing that he was being charged for an additional homicide. As it turns out, there was an open case that happened a month earlier “on the same block, in pretty much the same space” as the crime for which he was already charged. Although Wendell firmly maintains that he was in no way involved, he was charged with this crime as well. “I have a vivid memory of [my lawyer] … when the judge asked me how do I plead with this case, he had to nudge me because I’m just, like, stuck. So yeah, I got charged with a second murder.”

Wendell was in disbelief as the charges stayed, both trials proceeded, and he was ultimately found guilty for two separate homicides. For the first, he received a 35-year prison sentence, and for the second, a mandatory natural life sentence without the possibility of parole. He remembers vividly how the judge said, “‘I wouldn’t give it to you if I didn’t have to, but I have to because this is what the statute reads.’”

Wendell felt angry and defeated. “At 19 years old, how else do you process something like that?” he asks. “You don’t have access to somebody telling you that this is going to be OK.”

“I’ve Never Accepted a Life Sentence as My Fate”

Wendell began his post-conviction incarceration at the now-closed Joliet Correctional Center. Going to prison for something that he didn’t do while also being inundated with the daily realities of danger and confinement left Wendell on edge and disillusioned. To make matters worse, the “same day I got there, someone just got killed,” he remembers. As soon as his six-month orientation period was up, he requested a transfer to Stateville Correctional Center.

At Stateville, Wendell met someone who changed his outlook, a big brother of a friend who was also in Stateville. He had heard that Wendell had just been transferred to the prison and called him to his cell. That first meeting, Wendell remembers his friend saying something to the effect of, “I’m gonna put some fat on your head while you’re here,” and began sending him books to read. “He didn’t have a GED, no formal education, none of that. Just totally self-educated,” Wendell explains.

After a while, Wendell began to sincerely enjoy reading. “It got to the point where I started liking stuff, different authors, and I started buying books and sharing with him,” he says. In addition to a love of reading, this friend instilled in Wendell a sincere and selfless desire to help others. He gave Wendell simple marching orders: ‘“Man, everything that I do for you, do it for someone else.’”

Wendell sees his mentor as a key figure in his life, at a time when he desperately needed some guidance. “He put his arm around me, man. Really pushed me in a certain direction,” he says. Reading books and staying focused on productive goals stopped Wendell from giving up entirely, despite the despair he felt at the very beginning of his incarceration. He saw firsthand how “sickening” the mentality of resignation was for people who had been incarcerated for decades by the time he entered prison, and knew that he wanted to have a better existence than that. “I’ve never accepted a life sentence in my fate,” he insists.

Networks of Support

Wendell was fortunate to have many other sources of support while incarcerated. His mother was a steady lifeline. “While I was in prison, she got her sobriety,” he explains. After that, he says, “she didn’t take a day off, not one. And I mean all the way up until today.” Likewise, Wendell’s grandmother was “there for me the whole entire time of my incarceration.”

There were other friends Wendell knew he could rely on, too. One was incarcerated with Wendell in Stateville and then released in the early 2000s. “He was a constant in my life,” Wendell says. “All the way until I came home, he supported me.” Another was a high school friend who stayed in touch and was a substantial source of support throughout his incarceration. “I’ve got a great appreciation for her,” he shares, and adds that these kinds of people are important because they “invest in you. Not just emotionally, but they invest in you financially, too.”

Wendell even recalls a correctional officer from Stateville who made a lasting impression. “We were around the same age when we started in there together, pretty much grew up in there together,” he says. “And she’s about to retire, and I’m just starting paying my taxes.” In spite of all of the “indoctrination” around “dealing with people that’s incarcerated” that corrections staff experience, Wendell felt like she always saw him as a whole person, worthy of dignity.

This kind of support and care was a critical part of getting through the horrors of incarceration. Wendell recalls soberly, for example, how the atmosphere of the prison would change when the Department of Corrections executed someone. Illinois executed nearly a dozen people in Stateville in the 1990s before moving executions to the now-closed Tamms Correctional Center, and then ending capital punishment in 2011. Wendell remembers that one of the telltale signs an execution was imminent was a shift in the food. “Every time there was an execution in the facility, they fed you really, really good,” he says. “It was burgers and fries, fried chicken, big ass pack of cookies.” He found the disconnect between the better food options and the gravity of the unfolding events to be “eerie” and “sick.”

Actual Innocence or Miller ?

Wendell knew that while he could and would advocate for himself to the best of his abilities while incarcerated, self-advocacy likely wouldn’t be enough to win the uphill battle to get released from prison and, hopefully, be awarded a certificate of actual innocence. He needed “a good lawyer to understand the issues I want to raise … and ultimately, that was what happened.” In 2008, Wendell’s good friend from high school paid his first big legal fee.

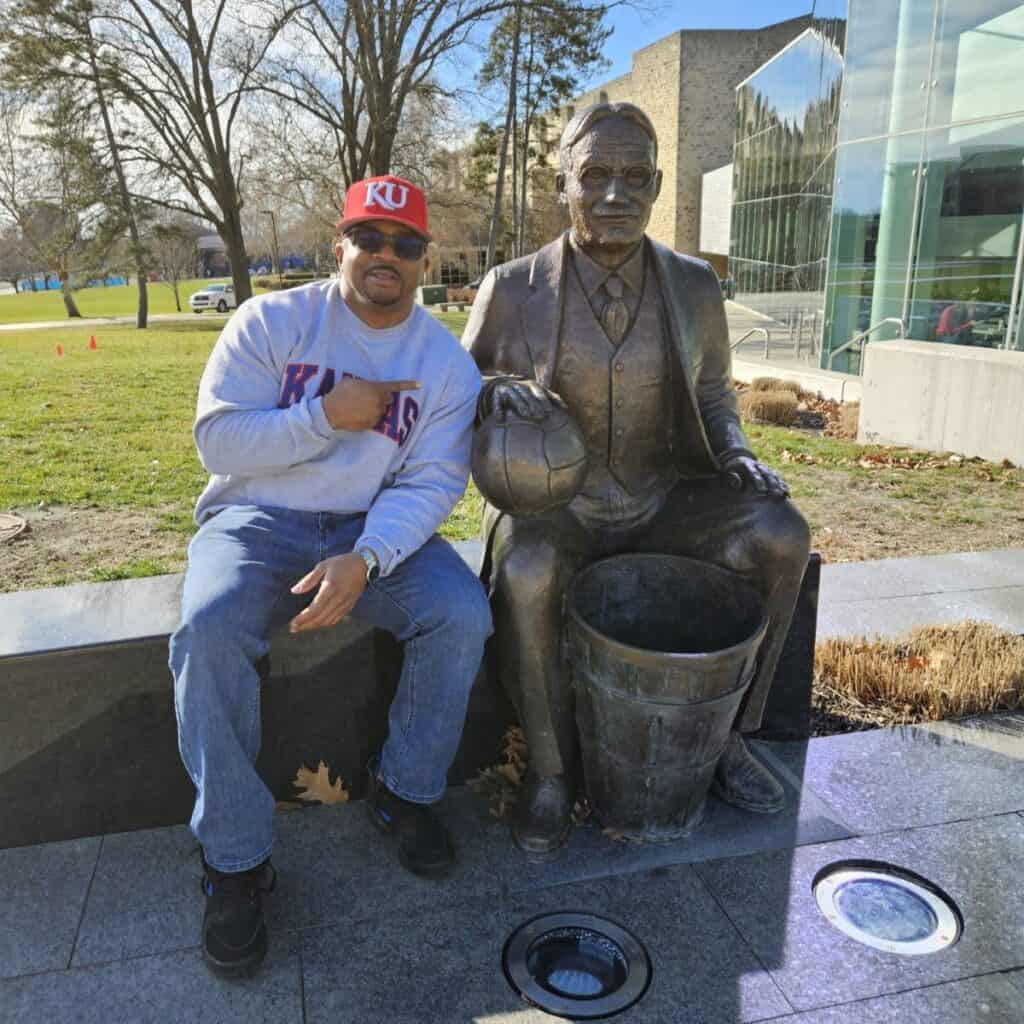

For the next decade, Wendell was persistent about pursuing actual innocence rather than trying to get time off his sentence. In 2017, at the end of a long appeal, he got “a ruling that was not in our favor.” It was another devastating blow in the grueling process of appeals. But unlike his earlier losses in court, this one came after the U.S. Supreme Court decision Miller v. Alabama, which ruled that juvenile mandatory life without parole sentences like Wendell’s were unconstitutional, and also after the Illinois court decisions made the ruling retroactive for people currently incarcerated. With some persuasion from friends in prison and after lengthy conversations with his lawyer, Wendell decided to pursue a Miller resentencing, even though it meant giving up his pursuit of actual innocence. “I came home on January 26, 2018 via Miller,” he explains. “It was something that I was so reluctant to do, but at the same time, it was a real-deal blessing in disguise.”

“Getting my Life Back”

Wendell explains that being resentenced and released from prison after initially being sentenced to natural life is like “just getting my life back, so to speak.” He adds that, “I have a different type of appreciation. I may value my life more, like, just a little bit more, because I know what it’s like to lose it, and then have to really, really fight, claw, scrape to try and get it back.”

The process of reentry, however, is also like having to adjust to an entirely new life. Coming home after being incarcerated for decades is a transition between two worlds: “literally growing up in this [prison] environment, becoming a man in this environment, and then to leave that environment and come somewhere totally different.”

One of the most difficult things Wendell has had to learn is how to have healthy conflict. In prison, conflict is “dealt with in one of two ways: it’s either, we’re gonna get it on, or I ain’t gonna mess with you.” It can be difficult to explain to people close to him that pulling away is how he learned to cope; the better of two ineffective options. “I don’t know how to convey, you know, that’s part of the trauma that I’m facing from that over there, so I just shut down,” he says. Nevertheless, he’s learning “how to just process stuff, but don’t allow it to fester.”

Shortly after coming home, Wendell got a commercial driver’s license (CDL) and drove trucks. While he really enjoyed certain aspects of the work, he couldn’t say no when Jobi Cates, the founder and then-Executive Director of Restore Justice offered him a different kind of job: to learn the ins and outs of nonprofit advocacy work. He quickly was promoted from Apprentice to Program Manager. In this role, he started an official apprenticeship program called Future Leaders Apprenticeship Program (FLAP) to employ people who just returned home after being in prison for decades, train them in nonprofit and advocacy work, and provide on-the-job technology and other professional development skills.

After another promotion to Program Director, he took the helm: in March 2024, when Jobi had to step down, Wendell became the Executive Director of Restore Justice. “On my reentry journey, there’s so much, there’s so many new lessons that happen almost daily, weekly,” he says. “And I’m so fortunate … I have access, right? I literally have a job where I’m learning every day.”

In this new role, Wendell is leading by example. “I never thought I could be an executive director or leader of a statewide organization. Me in this role gives me a different sense of hope to system impacted people … [and] I lend a level of lived experience to this role,” he says. “This next chapter is just an example of the vision of our founder, and I am just pleased that I can lead Restore Justice.”

Paying it Forward

Wendell often thinks back to the advice he received from his mentor in prison: ‘“Man, everything I do for you, do it for someone else.’” While incarcerated, Wendell took this precept seriously, understanding his mentor to mean: “if you’re in a position and see young guys coming to prison, give them some direction and invest in them.” This is what his mentor had done for him, and this is what Wendell did for teens and young men coming into the prison for the first time. “He was telling me to grow and how to grow,” Wendell explains. Now, six years after his release, this call to action has a new meaning, with the creation of FLAP and his leadership of Restore Justice.

Wendell was a part of Restore Justice’s legislative successes in 2019 and 2023, when youthful parole opportunities were enacted for virtually all people under 21 in Illinois going forward: Illinois became the 26th state to abolish juvenile life without parole sentences. Wendell knows the positive impact this kind of legislation will have on individuals, families, and communities firsthand. “It’s phenomenal just to see how some of the things that [former “juvenile lifers”] are part of in different parts of the country, some of the things that they’ve been responsible for, participating in, and just the vision,” he says.

But Wendell also knows that the work is far from over, and the fight doesn’t end with people under 18. “There’s quite a few people that I know that didn’t meet that threshold [for Miller] … they’d just turned 18, by a few days,” he laments. “Then I’ve seen people that were sentenced under Truth-In-Sentencing, right, that may have received a sentence of 39 years, so they can’t get relief from Buffer,” Wendell explains, referencing an Illinois court decision that ruled that sentences over 40 years counted as de facto life sentences. Despite all the technicalities keeping these people in prison, “they are more than worthy of getting relief,” Wendell insists. Under his leadership, Restore Justice will focus on retroactivity to ensure that people incarcerated before 2019 and 2023 can also benefit from the new parole opportunities.

In the end, work in service of others simply comes naturally to Wendell. “I just feel like real growth is contingent on creating opportunities for others,” he asserts. “That’s kind of like, in a nutshell what it is that I do. … If it’s going out partnering with other organizations, if it is me finding resources for certain things, it’s about creating opportunities. I think the more opportunities you create for people, the more you grow. That’s what I’ve been so blessed to do, and what Restore Justice does is create opportunities for people.”

More from the “more than a conviction” project

up next

Read the story of another returning citizen who was sentenced to juvenile life without parole and is now free

Read anotherread other stories

Discover the impacts of juvenile life without parole sentences in Illinois from additional perspectives

Learn morereport

Read the Restore Justice report on juvenile life without parole and extreme sentencing in Illinois

read the report