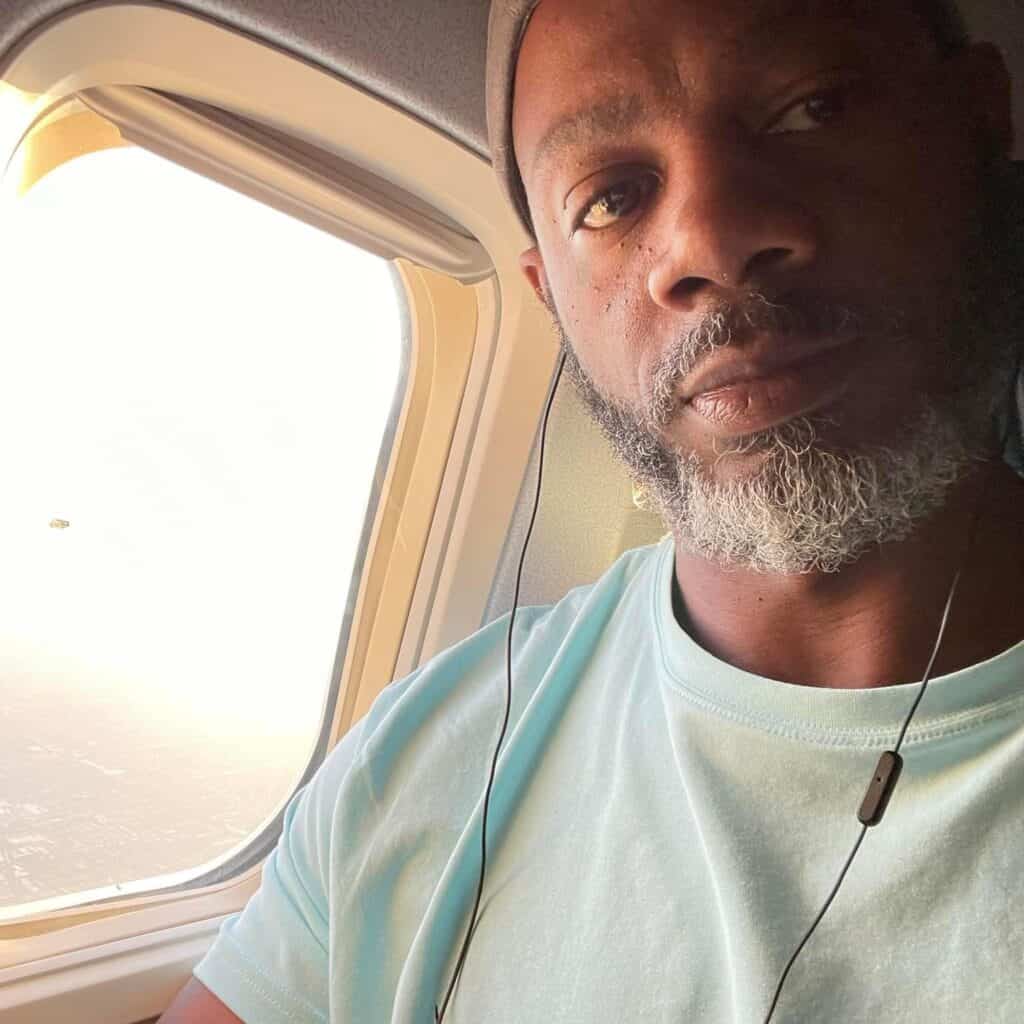

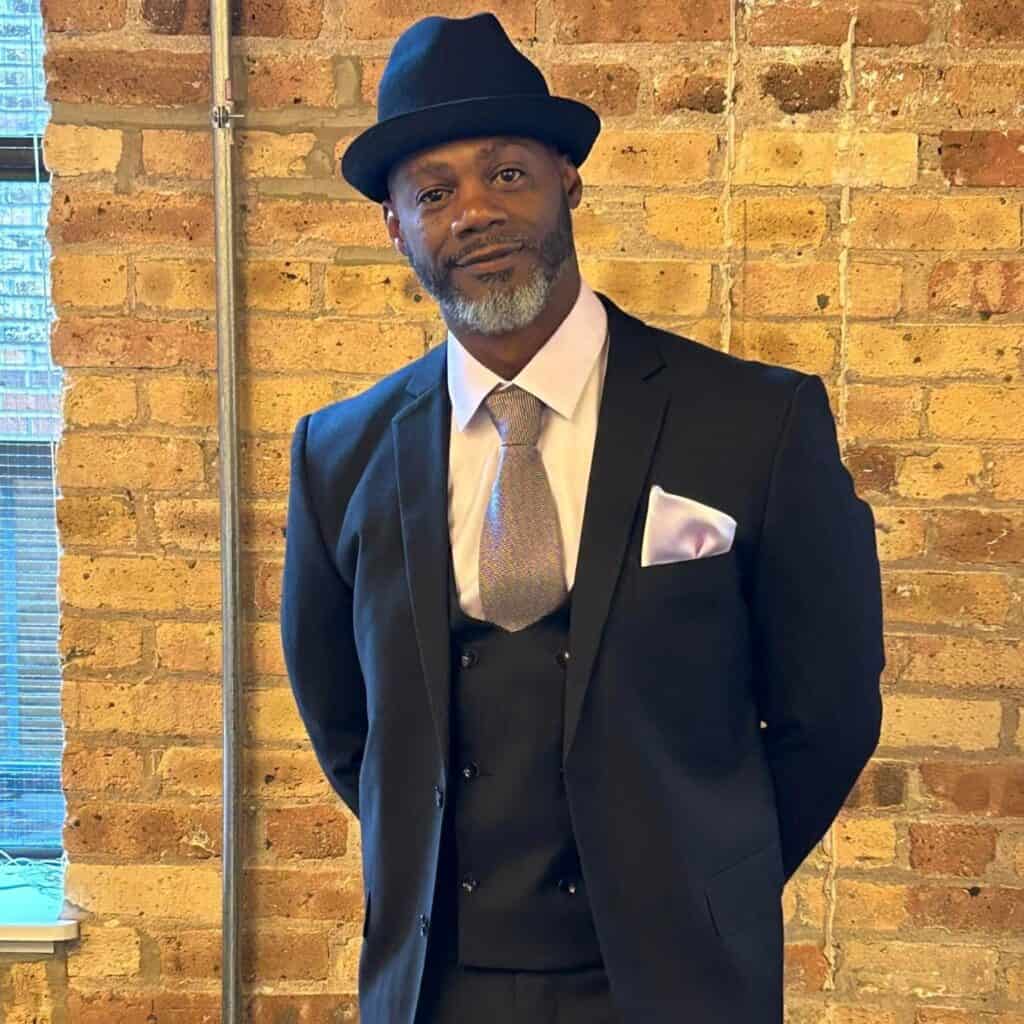

Nelson Morris

Nelson Morris was sentenced to die in prison for crimes he committed when he was just 17 years old. Now home after 29 years of incarceration, he strives to be his best with the opportunity he’s been given.

“I didn’t come home to hurt anybody. I came home and became a father to my son, and I became a grandfather to my grandkids. I’m a great friend, I’m loyal as hell. And I play a part in getting people home. I’m good enough with that.” – Nelson Morris

Nelson Morris explains what it’s like to be incarcerated with a natural life sentence with a profound, yet simple analogy: it’s like being covered with a sopping wet blanket. “You can maneuver, but you’ve got a wet blanket on, so you never forget that.” Several years after his release, Nelson still feels the weight of his life sentence. Nevertheless, he remains hopeful that reform is possible.

A Cycle of Violence

Nelson was fiercely independent as a child and teen. Some of his earliest memories revolve around his daily commute to school in the third grade, which involved taking a lengthy bus ride by himself. Being self-reliant, however, was more of a necessity than a choice. His mom was young and trying to make ends meet. She “always kept a job, sometimes two,” he recounts. “My father wasn’t really around,” noting that as a Belizean who could only come to Chicago on occasion, his father was “in and out of the country.” He characterizes his parents’ relationship as good, though inconsistent.

Reflecting on his childhood, Nelson now connects his early autonomy and the difficulties of his teenage years. “I spent a lot of time by myself,” he recalls, “so I think that’s how the streets came to play … I grew up in the neighborhood.”

As a young child, Nelson and his mom lived in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood. When he was in fifth grade, they moved to Englewood, “a very poor and violent area.” By high school, he was selling drugs. “I got robbed,” he explains, “and that was the first time I really, really got a gun. So when they came back to rob me again, things went wrong.” Nelson was 17 years old.

After his arrest, Nelson remembers the officers “locked me up in a room, [and] kept me there for a couple of days, handcuffed.” His previous interactions with the police exacerbated an already tense situation. “I was really kind of, like, closed off. I knew that I was in serious trouble … [but] we learned at an early age not to trust the police.”

As someone under 18, Nelson didn’t know the extent of his rights while he was being detained and interrogated, but he knows now he should have been treated differently. “They questioned me without my mother; they questioned me without a youth counselor,” he remembers. He was ultimately charged and convicted of two homicides and sentenced to natural life, the mandatory sentence at the time — regardless of age — for anyone with more than one murder conviction.

“Sitting in the Cell Was the Hardest for Me”

Nelson was 21 by the time he was transferred to a state prison after his sentencing. Even then, he was intent on staying under the radar. “I never really got into a lot of trouble. I never had a violent ticket,” he shares, referring to the disciplinary write-up for rule violations. He realized early on into his sentence that making waves affected eligibility for work assignments, and having lots of downtime made prison even more miserable. “When I couldn’t work, that’s when my time was hard … It was excruciating. I hated lock downs. I hated not having a job. I didn’t like just sitting in the cell.”

In order to stay busy, Nelson took any job he could get. “I did everything from waxing floors, to cleaning the death penalty room, to being a secretary for the sergeant … I worked in the gym, the kitchen, a cell house doing floors, [and] in the office of the commissary cooking food.” Despite the undeniably distressing nature of some of these jobs, Nelson still found working better than being confined to a cell.

The Inhumanity of Incarceration

Over the 29 years he was incarcerated, Nelson spent a significant amount of time in a handful of prisons across Illinois. “The one common thing in all the prisons,” he reflects, “was that they all treated you as less than. I’ve never been to a prison where they treated you like a person, like a real person.”

Many common occurrences regularly left Nelson feeling deprived of dignity. “Just psychologically, to have to use the bathroom in the open room…” he trails off. “And they will stick you in segregation [solitary confinement] for putting the curtain up, just to have your modesty.”

In addition, Nelson describes how incarcerated people were regularly humiliated as part of “shakedowns” — the searches and confiscations of property belonging to people incarcerated in the prison. In the Illinois Department of Corrections, the notorious tactical teams that conduct such searches are called the “Orange Crush” for their signature outfits of orange jumpsuits and riot gear, and their technique of lining people up. “Your hands are behind your back. And there’s another guy, and you got to be right up on him. So, basically, his hands are almost touching your privates and vice versa, and you got to be right up on him. And you’ve got to look down,” Nelson explains.

Nelson asserts that “they had an ‘Orange Crush’ in every prison,” which underscores the widespread use of this kind of humiliation as a means of enforcing strict power dynamics across the state. Lawsuits have been filed on behalf of numerous men and women incarcerated in Illinois, arguing that clients’ rights against illegal search and seizure as well as cruel and unusual punishment were violated by the ‘Orange Crush.’

While Nelson felt less than at every prison, he also recalls how the level of racism he experienced changed based on the culture of the facility and the broader external community surrounding it. His experience in Stateville Correctional Center, located just southwest of the city of Chicago, was very different from his experience in Menard Correctional Center, a downstate prison only about 60 miles outside of St. Louis. By Nelson’s approximation, Stateville had a majority Black staff, which changed the dynamic of interactions between correctional officers and people incarcerated. “Staff didn’t necessarily treat me like I was shit,” he notes about his time in Stateville. “Maybe because when they saw me, they saw their brothers, they saw their son, you know?” By contrast, Menard “was southern, and it was openly racist,” he explains. Corrections staff had “no problem letting you know how they felt about you … you really had to know how to maneuver in Menard.”

A Crack of Light in a Dark Tunnel

The harsh reality of a life sentence made any amount of optimism elusive for Nelson. “You’re going through this, what feels like a lifetime of heartache,” he says, “and you see no light at the end of the tunnel.” The absence of any pathway for release led some to despair. “I know guys who threw away their transcripts because it was that bleak,” he adds, referring to the written report of all court proceedings needed to file petitions or appeals. In Illinois, people receive one full copy of their transcripts after conviction, but must purchase any additional copies, which can cost many thousands of dollars.

Nevertheless, Nelson did everything within his capacity to pursue opportunities for release. “My transcript was like my Bible,” he attests. “I’ve been through this hundreds of times and trying to find something in this stack of papers to get home to some kind of life. It’s depressing, because the words on the paper don’t change. … I was guilty.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2012 decision Miller v. Alabama, which ruled that mandatory life sentences for people convicted of crimes that occurred before the age of 18 were unconstitutional, changed everything. “When Miller came it was literally like looking into the tunnel and seeing a crack, like, ‘Is that a little light? Huh! I ain’t seen that before!’” As a result of Miller, Nelson’s age was finally considered in a resentencing hearing, and he was released from prison in August 2020.

“Everything Is New Because I Got Locked Up So Young”

Now that he is home, Nelson faces many challenges related to readjusting to a changed society, a process that can be significantly more difficult for people incarcerated in their youth and for extended periods. “There were no sensors in the sinks [in the 90s],” he notes. “And so I came home, and there were no handles to wash your hands. And everything was [pay by] card … there were cellphones, texts. It was such a dramatic change for me that it was really hard to adapt.”

But technology hasn’t been the only unpredictable aspect of the outside world. Nelson has also found relationships with friends and family to be more complicated than anticipated. While in prison, he didn’t have a lot of contact with people on the outside with the exception of a select few. “I didn’t call other people when I was locked up because I felt like, ‘I got forever. What’s the purpose?’” He acknowledges, however, that his mother, ex-wife, and son were his pillars. “My mom always made sure I never needed,” he says. Nelson is now adapting to the new reality that he can form lasting relationships outside the prison walls. Nevertheless, relationships are undeniably different than they once were. For one, Nelson’s mother passed away in December 2010, which was an excruciating loss while he was still incarcerated.

There are a lot of other family and friends in Nelson’s life, though he says that it often feels like people still “see you a little different” after returning home from decades in prison. “You’re the young kid you were when you got locked up” in their eyes, he explains. This dynamic gets old quickly, and “you just lose the desire to be around people who look at you as the old you.” In the end, Nelson falls back on that independence he developed in his childhood. “The new car smell is gone … I’m good with just watching TV, being at home,” he concludes. “I’m OK with just being on my own.”

Restricted Freedom

On top of adapting to new environments, relationships, and skill sets, Nelson also lived under strict parameters dictated by the Illinois system of Mandatory Supervised Release (MSR), under which people who have just been released must be watched closely. Being violated, or not complying with the conditions of release, can result in severe consequences, yet explanations of these conditions are often cursory and confusing.

So when Nelson moved to a different neighborhood not long after his release from prison, he was unaware that he needed to formally register his new address as soon as he moved, rather than at his annual registration. “I went to register, and (the police officer at the precinct) locked me up.” Nelson spent three nights in jail for a supposed registry violation of not reporting properly.

Thankfully, the judge who presided over Nelson’s hearing was empathetic. He said, “‘Mr. Morris, get your stuff together by the next court date and I’m gonna throw this out.’”Nelson felt validated by the judge’s reaction. “It was just such an asinine reason to be locked up and I was doing so well. I didn’t do anything wrong, except not letting them know I had moved in the neighborhood.” Freedom under these circumstances can feel tenuous, at best.

Traffic stops ar e also anxiety-producing for Nelson. He is fearful of how police officers will see him, not just as someone with felony convictions, but also as a Black man. “You’re hearing all this stuff about police killing people, [so] you’re naturally paranoid anyway,” he explains. Yet, there’s only so much in an interaction with police that Nelson can plan for and control. When he was stopped the first time, he realized the best approach was to talk to the police like they’re fifth graders. “‘My ID’s in my back right pocket in my wallet. Is it OK if I get it? I’m reaching for it right now.’ … They think you’re being condescending. No, there’s no room for mistakes.”

“Let Me Be My Best”

Despite the difficulties of reentry, Nelson feels fortunate to have been given an opportunity to demonstrate his growth. “To be one of the ones that made it out here, I feel extremely lucky,” he remarks. Still, he admits that this feeling of fortune also sometimes comes with tinges of guilt. “I heard somebody use the phrase, ‘survivor’s guilt.’ I never understood it until now, because I have guys that call me regularly that have the kind of [prison] time I had, same cases, and the only thing different is they were born two months too late [to be Miller-eligible]. You feel guilty for being here, so you just really want to do your best.”

Lived experience makes Nelson a natural mentor to others navigating the complex world of reentry. “I think it’s imperative that we start helping more guys when they come home with the little stuff: IDs, technology, and driver’s licenses,” he asserts. “Somebody that can give them a pull up before they come home. Somebody to hold their hand when they come home. And somebody who kind of knows the system to help them navigate through registries and that type of stuff.” As much as he is able, Nelson is this guide to those who need it.

When it comes to helping youth from his neighborhoods on the South Side of Chicago, he is confident that spending the time to listen and providing safe spaces after school can go a long way. “I think that young kids think that nobody cares,” he asserts. “They need somebody to say, ‘I understand. I get it.’” But the other crucial need is for kids to have other options and opportunities for how they spend their time outside of school. “I really believe that when you leave a kid to their own devices, bad stuff happens,” Nelson says. “I used to go to [a school that] had this youth center, and it stayed open from like 3 PM to 9 PM. … When they closed that youth center, I started hanging out, I started selling drugs. Think about this: when I had something to do, somewhere to go, I didn’t get in trouble.”

Nelson hopes that sharing his story will increase awareness and support for systems changes that gives everyone a chance to learn from their mistakes and grow. “This stuff crosses social lines, it crosses racial lines,” he says. “Anybody’s child could get caught up and make the wrong decision.” As a Represent Justice Ambassador, he honed his storytelling skills to use his experience as a so-called “former juvenile lifer” to help advocate for criminal legal reform. Similarly, as a former Future Leaders Apprentice at Restore Justice, he told his story to legislators across the state and contributed to the successful passing of HB1064, now Public Act 102-1128, which created parole opportunities for virtually all people under 21 going forward. “Our story is in demand because you don’t have a lot of people that can say, ‘I’ve been on both sides. I had forever, and now I don’t,’” he explains. “So it’s rare to come up from under that and be able to talk about it.”

More from the “More than a Conviction” Project

Up Next

Read the story of another returning citizen who was sentenced to juvenile life without parole and is now free

Read moreOther Stories

Discover the impacts of juvenile life without parole sentences in Illinois from additional perspectives

Learn moreReport

Read the Restore Justice report on juvenile life without parole and extreme sentencing in Illinois

Read the report