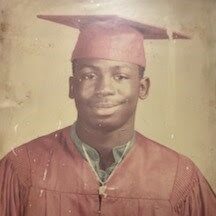

Michael Wages

Michael Wages was incarcerated from the age of 15 until he was 42. In prison, he never expected to have the life he leads now, but he’s learning to embrace the joys and challenges of reentry.

“I have yet to learn where I’m going. I just take each day step by step, not trying to run through it; try to learn and take some from each day and each person I meet. If I fumble, I fumble, but I did learn something along the way.” – Michael Wages

Michael sees an enormous difference between the person he was at 15 and the person he is today. “Young Michael, he was the drug dealer, the fast money,” he says, “but he was also vulnerable.” Today, he is more mature and measured, but the trauma and unpredictability of incarceration left their marks. “If you drop a dime or penny, or your shoe’s untied, or your nail breaks, I’m paying attention to it just because I don’t know what’s next to come,” he explains. As Michael adjusts to life on the outside, he’s finding the balance between healing and thriving.

“I Didn’t Care Much About Life Before I Got Locked Up”

Michael’s childhood was “a piece of work.” He grew up on the South Side of Chicago in the Ida B. Wells Homes, a now-demolished public housing project in the Bronzeville neighborhood. As a child, he often felt singled out due to colorism within his family. “I’m the only dark-skinned child my mother had compared to all my brothers and sisters,” he says. “So I felt like I was the black sheep of the whole family … it was eight of us in the house, but I was the one that was basically walked over a lot.”

As a result, Michael spent a lot of time outside of the home. “I started selling drugs when I was 10 years old,” he says. “You know how you want all the stuff you see other people wearing and all that? My mother told me if I wanted it, I had to go get it.” He joined a gang at 10 and climbed the ranks. “At 12, all hell broke loose,” he explains. “I would fight tooth and nail with anyone. My mother couldn’t control me.” He was kicked out of high school at 14 “for fighting another rival organization, out on the street, me and about seven of my friends,” he explains. “Then I never went back to school.” In part, Michael sees his early teens as a period of self-destructive and self-harming behaviors. “I didn’t care much about life out there before I got locked up,” he says.

“They Took Me and Locked Me Up”

No longer in school by age 15, Michael became even more involved in the gang. After a shooting at the Ida B. Wells Homes in August of 1990, rumors of his involvement spread. “Some guys, they had the impression that I did everything,” he explains. “They tried to retaliate, so they shot at the back of my building while I was going in it.” Fearful of what would happen next, Michael’s mother called the police asking for some kind of protection. “She called them to tell them to help me,” he says. “And they took me and locked me up.”

At the police station, Michael was quickly separated from his mother. “I was in a room with my mom for a minute,” he says. “And they told her, ‘We want to talk to him and bring him back.’ I never came back out of the room. They handcuffed me to a table and told me I was being charged with a double murder … I heard her scream.”

On top of everything else, Michael had great difficulty accepting that it was his mother who called the police that day. “For so many years I blamed her,” he notes. “It hurt because I felt she turned me in, and all the time she was just trying to protect me, not knowing what to do.”

After his arrest, Michael awaited trial at the Juvenile Temporary Detention Center, also known as the Audy Home. He remembers feeling like he wasn’t seen as a child in need of help, but rather a villain. During his trial, Michael did not recognize the person the state prosecutor portrayed him to be. “She made me out to be the biggest notorious person ever to commit a crime, and I’m 4’11”,” he says. “She made me the enemy to society.”

A couple of months before his 17th birthday, Michael was found guilty and sentenced to natural life in prison, the only possible sentence for someone convicted of two homicides in Illinois at the time.

“We Are Lost Causes in the Department of Corrections”

During the first few years of his sentence, Michael struggled to find his way. He began his sentence at “Little Joliet,” the now-closed Illinois Youth Center that was Illinois’ only maximum-security facility for boys, where he remained active in his gang.

After moving to “Big Joliet,” the now-closed Joliet Correctional Center, in his 20s, Michael began to question his involvement in the gang. “I was seeing a lot of things that wasn’t actually, quote-unquote ‘right’,” he explains. There, he saw the normalization of extortion as well as sexual and physical violence, and he came to realize the extent of the harm and suffering inflicted on people due to gang affiliation alone. Michael decided he no longer wanted to participate in this abuse, which made him a target of the gang. By 21, he had spent a lot of time in “seg” (segregation, or solitary confinement) for “fighting my own gang members, just trying to keep a level head.”

Even after he left the gang, Michael’s incarceration continued to be marked by difficulty. While at Joliet Correctional Center, Michael’s mother was banned from visiting for five years. “She came to visit me and she had one of my sister’s coats on,” he explains, which the guards claimed smelled of cannabis. “No marijuana in it,” he recalls, “it’s just the dog smelled her from coming in. And they restricted my mother for five years.”

Michael also felt helpless after the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) prohibited him from donating a kidney to his gravely ill sister. “They told me I was a ward of the state and I couldn’t give my kidney,” he explains. He wrote to the warden, the governor, and legislators in Springfield, but to no avail. Fewer than half of the nation’s 53 carceral systems (the 50 state prison systems plus the Washington, DC jail, the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers) have organ donation and transplant policies at all. Although the Illinois Department of Corrections does have a policy, it wasn’t in Michael’s favor: the policy prohibits people who are incarcerated from donating while living (even to family) and has no policy regarding posthumous donation. “I was willing to give my sister Betty whatever I had,” he says, then adds angrily, “She’s on her dying bed, and you’re telling me I can’t help my sister?” Deprived of bodily autonomy and the ability to provide a life-giving gift to a loved one, Michael felt dehumanized.

In fact, Michael felt degraded and belittled throughout his 27 years in prison. This was perhaps no more apparent than at Menard Correctional Center in downstate Illinois. “Menard is worse than any penitentiary,” he stresses, adding that people who are incarcerated there are regularly “treated like cattle,” particularly people of color. Racism was blatant and frequent; Michael recalls the everyday use of racial slurs by correctional officers as well as regular prejudicial treatment. “Say, like, a cell toilet don’t work. [Black people] get those cells until they get it fixed. If we go into the shower, most times we get the bad shower heads and stuff.”

To add insult to injury, Michael’s circumstances in prison were additionally difficult because of his life sentence. “Nobody cares about us. We are lost causes in the Department of Corrections,” he says. “You got life in prison, you’re gonna die here. That’s the way they look at us … the lost causes.”

The Bonds of Juvenile Life Without Parole

In order to get through his time in prison, Michael relied on the support of others. “When people [ask] how’d I make it, I say family,” he notes. “I’d say God, but God provided me the family to make it.” His mother, in particular, was a critical lifeline. “Everything that broke, she built me,” he emphasizes. “Everything that they tried to take away from me, I looked to her, just, gentle voice to get it back. … Without her, I’d been worse off.”

Another vital source of support was the community of people also sentenced to life without the possibility of parole as children. “Each and every one of us had our own characteristics,” he says. Yet, “we knew with each other we were stronger than apart, and that’s all of us with life without parole as juveniles. Even the older guys saw our bonds.” Michael turned to these fellow so-called “juvenile lifers” for inspiration and advice, and could also rely on them if the need arose. “You could be 16 buildings down. You tell us you hungry, we’re gonna find a way to feed you,” he emphasizes.

This group of “juvenile lifers” became a kind of family in prison. “We can call home to our family,” he says, “but when that phone hang up, I gotta turn to y’all because y’all all I got.” He recognized that responsibility and did his best to mentor younger people entering the prison. “I tried to be a positive influence for people after me that came in and that was younger,” he explains, “because it was a lot of older brothers that, like I say, taught me lessons … I didn’t want to learn in so many ways.” These relationships were so important at such a crucial point of his development that Michael credits them with his growth. “My incarceration, it made me the man I am because I met them,” he insists. “It made me stronger mentally and physically. Spiritually, I can only give that to God but God put each and every one of those individuals in my life for a reason.”

Thanks to the support of his family inside and outside of prison, Michael was encouraged and motivated to pursue the educational opportunities available to him. He was 21 and a half when he got his GED in prison, and was a top student. “I got the high honor roll certificate and a presidential award,” he says. He also obtained additional certificates over the years, including a paralegal certificate, a commercial custodian certificate, and a building maintenance certificate. Yet in so many ways, Michael’s ability to achieve and persist among horrific prison conditions happened in spite of the failures of the system, not because of its success.

“I Know Where I’ve Been, I Have Yet To Find Out Where I’m Going”

Thanks to the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Miller v. Alabama, which ruled that mandatory life sentences for children under 18 were unconstitutional, he was resentenced and given an out date. Initially, Michael was skeptical of the case’s impact on his sentence. At the time of the ruling, 22 years into his sentence, he’d come to accept that he was going to spend the rest of his life in prison. “I am not gonna lie, I was the one nonchalant,” he says of his reaction to Miller. He was certain “we ain’t got a chance in hell.”

Nevertheless, Michael was released from prison in 2017. Adjusting to life on the outside has been a challenge. For the first three years, he was on house release, also known as home detention, which “was painful.” As a condition of Michael’s release, the arrangement put restrictions on his freedom such as a curfew. Michael was also working multiple jobs in the beginning, which gave him little time to enjoy his freedom.

His hectic work schedule became truly unsustainable when his mother fell sick with pneumonia. “I quit my job because I was a walking zombie,” Michael explains, between working long hours and spending the time he wasn’t working or sleeping at the hospital.

Since then, Michael explains, “My journey, it’s just getting started.” Michael and his wife started their own business doing parties. “She came up with the bright idea … I can cook, so we’re going to cater,” he says. He is also working at his daughter’s clothing shop.

Being home has also come with an abundance of joy. Michael is “blessed with a wife, three beautiful kids — well, they grown now, and bigger than me, too — nine grandbabies, and a mother who’s still around.” He gives thought to how his life trajectory has been unpredictable, to say the least. “I can’t actually say I expected any of this,” he explains, “but I embrace it wholeheartedly.”

Today, Michael is more self-aware than he was in his early teens and hopes to help others learn about the unconscious behaviors and larger social systems at play in daily life. “We do things that we’re not aware of,” he explains, which can lead to becoming “trapped in situations that we don’t understand.” He is also more attentive to and educated about the complexities of the criminal legal system and how everyone is vulnerable to it. “They can arrest presidents, they can arrest governors, and the rest. So we need to be more educated about that part of life.” He concludes, “Let’s educate each other on the system and love. Everything else, it’s gonna fall in its own place.”

More from the “More than a Conviction” Project

Previous Story

Read the story of another returning citizen who was sentenced to juvenile life without parole and is now free

Read moreOther stories

Discover the impacts of juvenile life without parole sentences in Illinois from additional perspectives

Learn moreReport

Read the Restore Justice report on juvenile life without parole and extreme sentencing in Illinois

Read the report