Leah Allen and Lydia Hill

Leah Allen’s son and Lydia Hill’s nephew, Marshan, was sentenced to die in prison at a very young age. Due to a change in laws, he was released after spending 25 years in prison. Since his return home, his mother and aunt are happy to see him rise above challenges to thrive as a leader and advocate.

“When they read his sentence, I cried. I felt like I was going to faint. I didn’t think he would get that kind of sentence because he had not really done anything. I was very emotional; everyone in the family was. … Even Marshan broke down. We didn’t expect that.” – Leah Allen

Leah Allen and her sister Lydia Hill were appalled and devastated when Leah’s son Marshan was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for his role in a double homicide. For over two decades, their support for him as he served his long prison sentence never wavered. Since his release in 2016, both women have continued to cheer him on throughout his numerous accomplishments and contributions to criminal legal reform.

A Nerdy and Compassionate Child

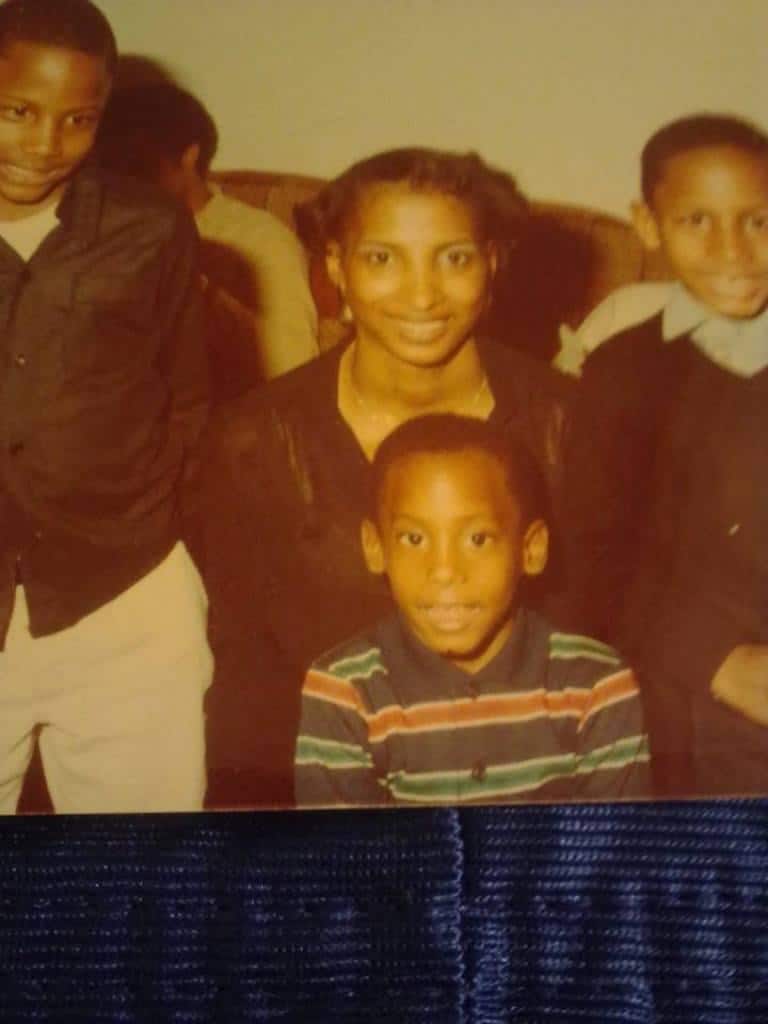

For Lydia, Marshan is more a brother than a nephew. She explains that as Leah’s youngest sibling, she was close in age to Marshan and his brothers, so “we grew up together.”

Leah and Lydia have fond memories of Marshan’s childhood: He was a very inquisitive child,” Leah says of her son. “He liked to explore and fix things.” Her sister Lydia concurs, adding, “Yeah, he was really smart. He was a quiet kid, a bit of a nerd. He paid attention to things. He liked to fix cars, so as a teen, he was hired at an automotive shop.”

Young Marshan was also a laid-back child who enjoyed hanging out with his brothers and friends. “I used to take him and his friends fishing and camping,” Leah shares. Her sister adds that he was compassionate; he did not want to hurt anyone. “There was a boy picking on him, hitting him, and he wouldn’t fight him back,” Lydia recalls. “My brother and I had to tell him, ‘Look, you have to fight him back, or he won’t stop hitting you.’ But he was not a fighter. He was not into harming people,” she recounts.

When Marshan was 15 years old, he stole a van, and his life took a turn for the worse. Marshan’s mother still remembers being at the police station when they brought him in. “The police were looking for my first son to ask about his involvement. I went to the station with my first son and a friend, who was also a police officer. They took my son to the back to question him,” Leah says. “As we were waiting for my son, they went to my house, got Marshan, and brought him in for questioning,” she continues. “I asked them, ‘By him being a minor, shouldn’t I be with him?’ They told me no. So he was back there being questioned without a guardian or without legal counsel,” she recollects.

With no attorney or parent present, 15-year-old Marshan was quite vulnerable, and police officers did not hesitate to use intimidation tactics to get him to confess to a crime he didn’t commit. “There was some mental brutality going on. I remember he told me they wouldn’t let him go to the bathroom. They wanted him to admit to the crime,” Lydia explains. She also reveals that years later, “some of these police officers got convicted of police brutality and for torturing people into statements.”

A Young Boy in Distress

Once Marshan gave his statement, he was not sent home as officers promised but instead taken to a juvenile detention center, accused of double homicide.

Leah and Lydia were just as confused as Marshan; they didn’t understand how stealing a van could result in double murder charges. They later found out that under the felony murder rule and the theory of accountability, Marshan was considered responsible for the homicides that were perpetrated by the people he transported in the stolen van, even though he did not know at the time they had committed a crime.

The two sisters visited Marshan at the juvenile detention center several times and then at Cook County Jail, where he was transferred after he turned 17. Lydia recalls it was overwhelming to see her nephew in distress. “Every time we left, he would shed tears,” she recollects. Court appearances were even more heartbreaking. “It was very sad and draining to see him go through these difficult times as a kid,” Lydia says. Physical restrictions that did not allow communication or contact worsened the ordeal. “To be that close to him as a child and not being able to at least wave or say hi was devastating.”

At the end of a trial, both women were exhausted, and the verdict was crushing: Marshan was sentenced to natural life without the possibility of parole, the mandatory sentence for double homicide at that time. The whole family was shattered. “I cried and felt like I was going to faint because I didn’t think he would get that kind of sentence. I was very emotional,” Leah remembers. “Everybody in the family was crying. Even Marshan broke down. We were shocked because we thought the lawyer had done a tremendous job, and we were hoping for something more positive,” she emphasizes.

As the reality of his life sentence settled in, Lydia became weary of what could happen to Marshan. “I was worried about him being in jail with people who could be really rough. I knew people who had spent a lot of time in jail. I heard their stories about prison. So, I was very scared about what could happen to Marshan in that environment.”

I Will Never Leave You

Visiting Marshan in prison throughout those 25 years was always dehumanizing. “Guards treated people who visited like prisoners. They were very rude. They didn’t treat people kindly and like humans,” Lydia says.

Yet Leah and Lydia were determined to visit and support Marshan regularly to ensure he never felt neglected or abandoned. “When he was still at the juvenile detention center, I made a promise to him: ‘I will never leave you. I’ll always be there for you,’” Lydia says. However, it was not easy to remain present and supportive. “I must admit it was not easy. Life got in the way. I went through hard times. There were moments I couldn’t send him money; there were years I didn’t even get to see him. So, he had some lonely times,” she recounts. “But we’d always reconnect,” she continues. “And when I had kids, I made sure I took them to see him. He watched them grow up, just like I watched him grow up.”

The family was dealt another heavy blow when Marshan’s elder brother unexpectedly passed away after a motorcycle accident. So, while navigating their own grief, Leah and Lydia endeavored to help Marshan cope with the loss. “He was devastated. That was his big brother and he looked up to him,” Leah says. Looking back, they understand how essential their assistance was. “It is important to support your incarcerated loved one because family is all they have,” Lydia says. “Marshan used to tell me stories about what was going on inside, and it was devastating. Having a support system to help him go through that was crucial,” she concludes.

A Chance to Come Home

While Marshan’s brother was alive, he paid Marshan’s legal fees. After his death and following disappointing experiences with various lawyers, Marshan decided to study law even though there were limited educational opportunities in prison. Lydia reveals that “he requested a typewriter. He was determined to do and learn so much that I had no doubt he would succeed.” Marshan completed his paralegal course and became a jailhouse lawyer, helping other people who were incarcerated file their petitions as well.

When Leah and Lydia learned about the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Miller v. Alabama, which made mandatory life without parole unconstitutional for children 17 and younger, they could not hold back their excitement. For them, this decision was a “chance for Marshan to come home.” Lydia emphasizes how Marshan had been so “diligent about his appeals that I knew he would find some ways for that decision to help him out.”

Eventually, Marshan was resentenced not only pursuant to Miller, but also to the Illinois Supreme Court’s decision in People v. Leon Miller, which made the multiple-murder sentencing statute for a juvenile convicted under the theory of accountability unconstitutional. In 2016, after spending 25 years behind bars, Marshan finally regained his freedom.

“The Dreams I Had Finally Came True”

The day Marshan was set to come home, his family rented a bus to pick him up. “We stood outside the prison all day, waiting. Later that day, a group of guys came out—no Marshan. We were like, ‘What’s going on? Why is he not in the group?’ They couldn’t give us any information,” Lydia recounts. Unfortunately, the family had to come back the next day with the hope that their loved one would be released. “We were just praying that everything would be fine and we won’t go through this again,” Lydia says.

Marshan walked out of prison amid laughter, cheers, and tears of joy. His release brought immense relief and happiness to his mother and aunt. “I used to have dreams about Marshan coming home,” Lydia says. “So when it actually happened, it was like, ‘Wow! This is not a dream!’ The dreams that I had finally came to a reality.”

One family member present that day was Lydia’s older aunt, who had assisted Marshan financially whenever she could and whose only prayer was seeing him get out of prison. “She used to say, ‘That’s my wish. I just want to be able to see Marshan come home.’ And in spite of her age and failing health, she was there. She took that ride; she stayed on that bus all day, and she was able to see her nephew walk through those doors.”

“It is so wonderful to have Marshan back,” Leah says. Now, she can communicate with her son without restrictions. “Just being able to talk to him and see him when I can is a blessing,” she comments.

A Man on a Mission

Leah and Lydia are extremely proud of what Marshan has accomplished since his return. They are amazed at his ability to overcome adversity, “When you come out of prison, people stereotype you. One of Marshan’s greatest challenges after coming home was people being able to accept him as a previously incarcerated person for 25 years,” Lydia says. “It set him back as far as getting a driver’s license, getting a job…” she trails off.

Reflecting on the issues Marshan had to juggle since his release, Lydia explains that society does not provide a supportive environment for returning citizens. “Society does not help them; employers do not support them. They have nothing when they get home. They don’t have the rehabilitation resources that they need,” she laments. “When you get out of prison, you need a strong support system because the transition is very difficult.”

Despite the hurdles, Marshan secured a good job in advocacy and is attending law school on a full scholarship. He wants to continue advocating for criminal legal reform in Illinois and practice law to help those who are still behind bars. Lydia says, “His determination is outstanding. He has goals, he has a mission, and I’m proud of him, of his focus.”

More from the “More than a Conviction” Project

Up Next

Read the story of another loved one who was impacted by the criminal legal system in Illinois

Read moreOther Stories

Discover the impacts of juvenile life without parole sentences in Illinois from additional perspectives

Learn moreReport

Read the Restore Justice report on juvenile life without parole and extreme sentencing in Illinois

Read the Report