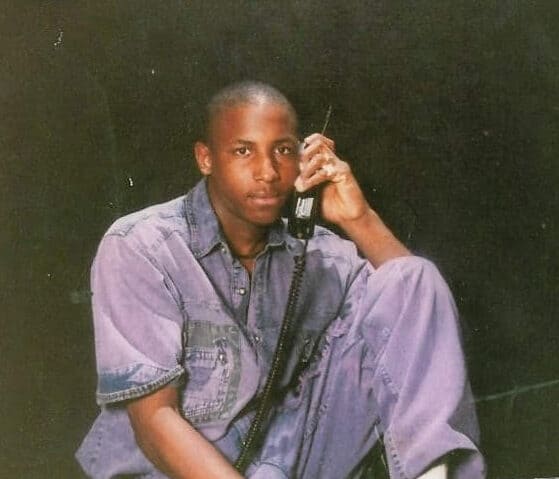

Marshan Allen

At just 15 years old, Marshan Allen’s life turned upside down when he was sentenced to die in prison. Now, released after 25 years of incarceration, he is a law student and accomplished advocate who fights on behalf of those still behind bars.

“Just imagine being a child, and one day your life seems normal and then the next day you’re snatched from everything you know: your neighborhood, your family, your friends, your school. And you’re snatched up and you’re taken and put into another environment, a hostile environment where you don’t know who’s your friend, you don’t know who’s a foe; you don’t know the rules, you’re not familiar with the culture, anything. And you’re made to navigate this on your own. It was scary.” – Marshan Allen

In prison, Marshan Allen spent a great deal of time thinking about and studying the law. Although his case and his sentence involved complicated legal doctrine that held him legally accountable for the actions of others, he quickly discovered that he was his own best advocate. Marshan became a certified paralegal, worked in the prison law library, and petitioned the court to review his case more than a dozen times. Eventually, he became a “jailhouse lawyer,” helping other incarcerated men navigate the legal system. After being released in 2016, Marshan extended those experiences and skills to the outside world. “This whole detour now led me to law school, and I don’t think I would’ve found my way there, absent what I went through,” he says.

A Childhood of Drugs and Violence

Marshan’s childhood revolved around his grandmother’s house in the East Chatham neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. His parents separated when he was about seven years old and later divorced. He remembers moving around with his two brothers frequently and then being raised mostly in a single-parent home with his mom. But his grandmother’s house “was always the center of action for the family,” he explains, and “it was the one house that was the constant in my life.”

Having lived in the neighborhood since the ‘60s, his family had deep roots in the community. After decades of white flight and disinvestment, the area had become “plagued with gangs and drugs and violence,” Marshan recollects. Several members of his family sold drugs and encouraged him and his brothers to participate. “Looking back on it now, I can see that it was not an ideal childhood. But I think that at the time I didn’t know, because I didn’t know anything else. It was normal for me.”

In 1992, despite being too young to legally drive a car, Marshan was involved in his older brother’s drug business as a carrier, doing the risky business of picking people up for drug purchases and then dropping them off. At one point, he was kidnapped and robbed at gunpoint, and there were moments during that traumatic ordeal at which he says he was “scared that they were going to shoot me or kill me.”

A few weeks later, just before his 16th birthday, Marshan stole a van, not knowing that the people who rode with him in the vehicle would later shoot and kill two others they believed were involved in that previous robbery. After the shooting, he remembers “being on the floor, covering up with my blanket, and just crying … because one, (I couldn’t believe) what had just happened, and I wasn’t sure how to process it. And two, because one of the guys who was killed was actually my classmate.”

The Unjust Realities of Felony Murder

Marshan was at home several weeks later when police arrived, put him in handcuffs, and took him to the station. Earlier that same day, his older brother and mother decided to go to the police station and explain his brother’s lack of involvement in the murders because there were rumors in the neighborhood that the police were looking for him. Marshan has a vivid memory of seeing his mother at the station and not being allowed to be with her. “My mom was on the phone,” he remembers. “We walked past the room, and the cafeteria has the glass. And I heard her say, ‘There go Marshan right there!’ And I heard the phone drop, and the police hurried up and ushered me to the back office area.”

Marshan, who knew little to nothing about the system or his own rights, found the experience to be overwhelming. “I asked for my mom; they wouldn’t let me see my mom. I asked to see my brother; they wouldn’t let me see my brother,” he says. “And I asked for an attorney, not really knowing …,” he trails off. “Seeing it on TV, when you ask for an attorney, (the police) stop talking to you; they leave you alone. But they didn’t do that. It didn’t work.”

Eventually, Marshan could no longer resist the mounting pressure. He remembers officers telling him the only way he was going home was to talk. “I ended up telling them what happened,” he shares, “that I stole the van. Not knowing that I was gonna be charged with murder for stealing the van. But that’s what they did … they took me to the juvenile facility that night and I stayed there about a year before I went to trial.”

Despite having no knowledge of the shooting before it happened and not possessing or discharging a firearm, Marshan was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without parole under the legal doctrine of felony-murder. This doctrine states that someone accused of a felony can also be charged with murder if that felony results in the death of another person. In other words, because Marshan admitted to the theft of the van, prosecutors argued that he aided and abetted the home invasion that resulted in two homicides and charged him with felony murder. In Illinois at the time, the mandatory sentence for a double homicide was life in prison without parole.

Marshan was prepared to be held accountable for stealing a vehicle. “I knew I had done something wrong and I should be held accountable for that,” he attests. But the somber reality of this sentence was beyond grasp. “I just kept thinking, ‘I just stole a van. I didn’t kill anybody. I didn’t hurt anybody. I didn’t have a weapon. I didn’t even know they were going to kill anybody,’” he stresses. “And they were trying to send me to prison for the rest of my life. And I just couldn’t accept it.”

Marshan was not the only person who found his case unjust at the time. His first trial resulted in a hung jury and a mistrial. “It was the lady on my jury,” he explains. “I think she was holding out for me, but she refused to find me guilty because she said that she thought the law … which allowed me to be found guilty of murder, was unfair.” By the time of his second trial, Marshan had turned 17 and was transferred from the juvenile facility to the Cook County Jail. “And then I was found guilty and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole,” he concludes soberly.

In that second trial, even the judge expressed regret at the extreme sentence being given to Marshan. As Marshan explained in a 2020 testimony before an Illinois Joint House-Senate Committee, “[The judge] gave me this sentence only because it was required by Illinois law. In fact, before imposing the sentence, the judge expressed disagreement with this mandate by stating on the record that if he had the discretion, he would have imposed a lesser sentence.”

Becoming a Jailhouse Lawyer

Marshan began his sentence at Pontiac Correctional Center, where he continued to grapple with the full weight of his sentence. “I had this naive belief that I was going to win my appeal,” he expresses. “So I had decided, I’m just gonna go and pretend like I’m away at college. I’m gonna go to school, and by the time my appeal comes through, I’ll win. I’ll have a college degree, I’ll be on my way home.”

But Marshan’s plan to educate himself did not go as expected. A 1994 crime bill (officially and inaccurately called the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act) ended need-based financial support for incarcerated students in Illinois. “I got to Pontiac in ‘94 … and then literally like a month or two later, that’s when the government had stopped the Pell Grants and the (Illinois) Department of Corrections decided to remove the college programs from the maximum security prisons in Illinois.”

With his plans squashed, it was difficult to find his way. “I fell into the culture of prison life, initially,” he admits. Still a teenager, he remembers spending a lot of time doing things he had enjoyed doing on the outside. “I always loved music,” he recalls fondly. “And I started collecting music cassette tapes and listening to music. I wasn’t really reading at the time. I had read a few books by that time, but I wasn’t an avid reader like I became years later.”

As the years went by, Marshan turned from music to books as he became more interested in law. Shortly after he was transferred to Stateville Correctional Center, Marshan, then aged 21, received devastating news; his brother had died in a motorcycle crash. The loss of a loved one while incarcerated is a unique kind of grief, and in Marshan’s case, was further complicated due to the support his brother had been providing. “He was the one who was paying for my attorneys and everything,” Marshan explains.

Even with his brother’s support, Marshan had become frustrated with his lawyer. During his trial and continuing into his appeals, the absence of compassionate and knowledgeable legal representation added to his distress. Ultimately, Marshan stresses that his defense lawyer “should have been an adviser, but he wasn’t.”

While he was incarcerated, disappointing experiences with lawyers continued. “My brother had hired a lawyer to help me with my post-conviction proceedings before he died. And this lawyer missed my deadline date,” Marshan points out. “He wouldn’t answer my calls; he wouldn’t answer my letters. He had all of my paperwork, so I couldn’t do anything on my own, and I was just tired.” Marshan’s mom wanted to help by raising money among their extended family to try to get a new lawyer, but Marshan knew the cost would be prohibitive, and he had reached a breaking point. “I said, ‘You know what, just send me the money. Give me a typewriter.’”

He enrolled in a paralegal correspondence course that cost about a third of his overall earnings from his job in the prison. “I wanted to get to take the course because I wanted to get a better understanding of the law,” Marshan explains. “I wanted to get into the law library, work there, and you had to have a paralegal certificate. And then I thought, ‘When I come home, I can use those skills to get a job as a paralegal too.’”

Marshan earned the paralegal certificate and got a job in the law library, which helped him confidently file more than a dozen petitions in his own case. “Every time the court denied it, I would read the order, go back, do more research, and pull out my typewriter, and type another petition,” Marshan says. This education also helped him become a “jailhouse lawyer” in the prison and “help guys out who didn’t understand the law and didn’t have a lawyer.” Transferring to Western Illinois Correctional Center later in his sentence allowed Marshan to take business management and computer technology classes and ultimately receive an associate degree while incarcerated.

“I Didn’t Want to Die There”

As someone sentenced to die in prison, the prospect of a life outside of the prison walls was precarious. “It was hard, the uncertainty of not knowing when you’re gonna come home,” he says, and the dehumanizing experience of incarceration, “makes it hard to hold onto your humanity in there because it makes you question your worth.” He concludes, “I didn’t want to die as an incarcerated person. I wanted to die free.”

Marshan’s studies and litigation efforts kept him busy, focused on the future, and able to hold on to hope for an opportunity at release. That hope was finally realized after Marshan received a new sentence in 2010. His resentencing was thanks, in part, to the decision by the Supreme Court of Illinois in People v. Leon Miller, which ruled that sentencing requirements applied to people under 18 who were also convicted under the theory of accountability were unconstitutional. After many years of appeals, Marshan finally came home in December 2016.

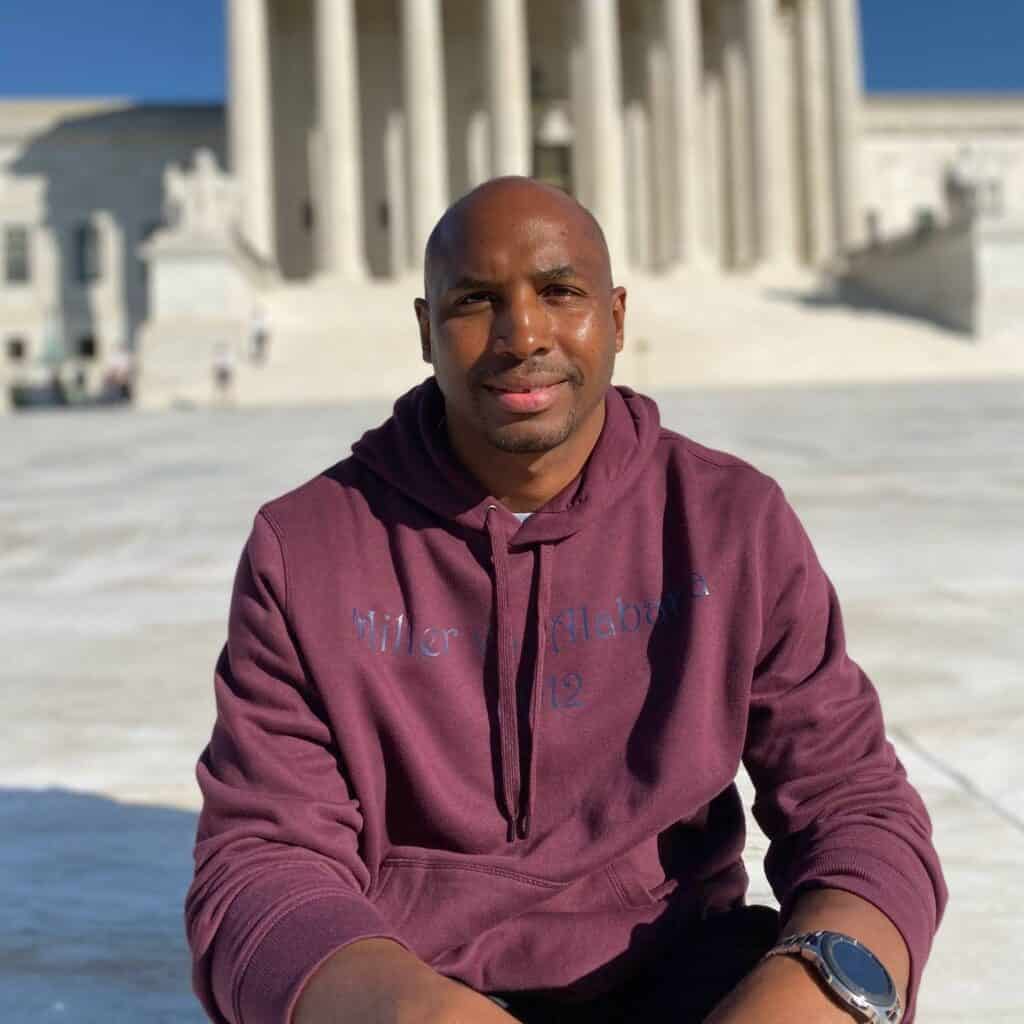

Advocating for Change with Lived Experience

Marshan has taken every opportunity possible to realize his professional and personal aspirations since being released. “It’s been six years and it has been a whirlwind … I’ve just been riding the wave,” he says with a smile. When he first came home, he started out as an analyst at a real estate appraisal company, then quickly took another job at a coffee shop, where it felt like he was seen as more than just his conviction and valued as a team member.

Marshan is committed to doing work that relates to his lived experience. Since working at the coffee shop, he has had several years of professional experience in policy work, advocating for criminal legal system reform with organizations such as Restore Justice, Fair and Just Prosecution, and Represent Justice. He also serves on a variety of boards and leadership councils. In January 2024, Marshan started a new role as the director of policy and communications at Illinois Prison Project.

In addition to juggling these commitments, Marshan is a law student, continuing down his path to a law degree that began while he was behind bars. While incarcerated, he used to discuss the possibility of law school with a close friend. “He and I used to talk about the law all the time, what we were gonna do,” Marhsan recalls. “Being in law school: It was a dream I had, learning the law.” He expects to graduate from Chicago-Kent College of Law in May 2026.

In his personal life, Marshan has also achieved many of the goals and milestones he imagined for his future self while incarcerated. “I always wanted to have my own house … and I do have that now. I wanted to get married. That was one of the things I dreamed about and longed for, was to find a mate that would really complete me … someone who cared about the world the way I did, cared about other people, and wanted to try to make a difference.” After coming home, he fell in love and got married to his wife, Tamala. They now have “three furry babies who are probably just as bad as my children would be,” he adds with a laugh.

All of this joy and achievement does not minimize the trauma of incarceration, nor the difficulties of reentry. But fortunately, Marshan is now in a position where he can assist those who are still incarcerated and create a more just and compassionate legal system through policy and legal work. “There were no lawyers in my family, definitely, and I didn’t meet any in my community. I had no desire to be a lawyer until I got incarcerated and started learning the law and realizing the need for those things I carry with me forever.”

Having been impacted by the criminal legal system, he is in a unique position to see the bigger picture and promote innovative solutions. “There are ways to hold people accountable for their crimes without locking them in a cage, throwing away the key,” he asserts. “We put people on the moon, we have done all this technology stuff; we can be creative enough to find other ways of holding people accountable for the harm that they cause.”

More from the “More than a Conviction” Project

Up Next

Read the story of another returning citizen who was sentenced to juvenile life without parole and is now free

Read moreOther stories

Discover the impacts of juvenile life without parole sentences in Illinois from additional perspectives

Learn moreReport

Read the Restore Justice report on juvenile life without parole and extreme sentencing in Illinois

Read the report