What is truth-in-sentencing?

Before 1998, people incarcerated in Illinois prison could proactively earn time off their court-appointed sentence through good behavior and participation in prison programming. Overall, these credits could reduce a person’s sentence by up to half, or a day off for every day in prison.

This system changed in 1998 with the passage of truth-in-sentencing (TIS) laws. Today, these laws limit the amount of time people convicted of certain offenses can earn off their non-life sentences.

People who are incarcerated may be broken into five “tiers” based on how TIS laws affect them, as follows:

- Day-for-day inmates may up to one day off their sentence for each day served (i.e. 50%)

- 60% TIS inmates must serve a minimum of 60% of their court-appointed sentence.

- 75% TIS inmates must serve a minimum of 75% of their court-appointed sentence.

- 85% TIS inmates must serve a minimum of 85% of their court-appointed sentence.

- 100% TIS inmates must serve their full sentence (100%) and are ineligible for any amount of time off due to good behavior or programming.

Originally, there were only 75%, 85%, and 100% tiers for TIS. The 60% tier was created through a bill passed in 2017 that permits individuals convicted of all offenses in the 75% tier (except gunrunning) to now earn up to 40% time off sentence, creating a new 60% tier.

As of last June, roughly one in three people incarcerated in Illinois were serving sentences affected by TIS laws. Figure 1 shows the distribution of these inmates into different tiers.

Figure 1. Individuals serving TIS-impacted sentences by tier

Caption. Data were sourced from IDOC’s public report on prison population as of June 30, 2017.

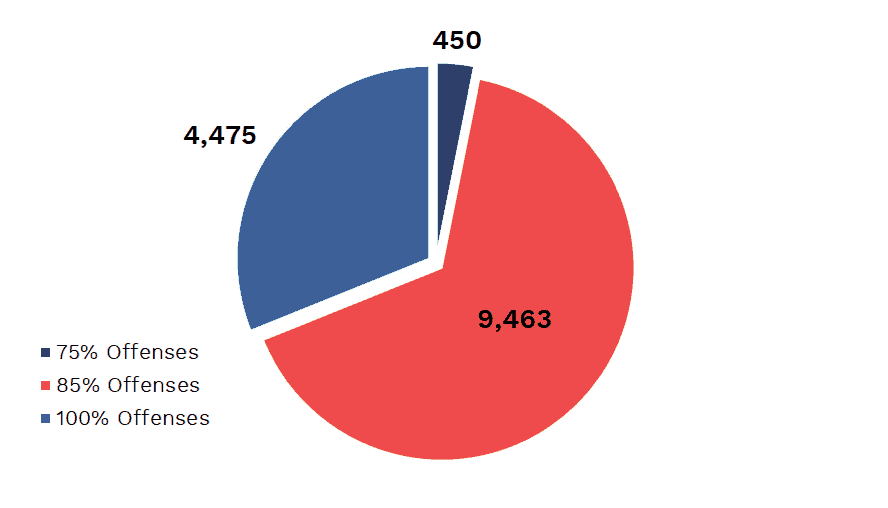

Most individuals in the 75% tier are serving sentences for drug-related offenses, while the 100% tier is comprised almost exclusively of inmates convicted of first-degree murder. Figure 2 shows the distribution of convicting offenses for individuals the 85% tier, the largest by population.

Figure 2. Convicting offenses of individuals serving 85%-TIS sentences

Caption. Data were sourced from IDOC’s public report on prison population as of June 30, 2017.

Why does it matter?

To some, the idea that inmates are able to earn time off their sentences might seem like a bug, not a feature. After all, why shouldn’t judges have the final say in how long a person serves? It was largely this idea—combined with the sense that justice systems ought to impose stricter penalties on more serious crimes—that led legislators to pass TIS.

But limiting the ability to earn time off sentence runs against the rehabilitative mission of correctional systems, nor is TIS required to preserve the power of judicial discretion.

Most individuals who enter prison will one day return to society. Therefore, restricting the ability to earn time off sentence through positive behavior and programs only teaches these individuals—especially those who enter as children or young adults—that the system believes them to be beyond reform.

Truth-in-sentencing only teaches individuals—especially those who enter as children or young adults—that the system believes them to be beyond reform.

The argument that TIS protects final sentences of judges from “circumvention” by sentence credits is also misguided. While it is true that numerous laws have reduced judicial discretion over the years, these changes—from automatic transfer laws to mandatory firearm enhancements–primarily work to prevent judges from imposing more forgiving sentences, not dispensing harsher ones.

For instance, a first-degree murder conviction carries a sentence of a minimum twenty years to a maximum of sixty years or life (before firearm enhancements). With such a broad range, judges that believed a longer sentence was justified could choose a sentence length toward the higher end of the range. TIS hardly seems necessary to ensure individuals serve longer behind bars.

Want to learn more?

One of the most troubling aspects of TIS is how it interacts with other “tough-on-crime” policies. Consider, for instance, how TIS combines with mandatory firearm enhancements and laws that allow automatic transfer of juveniles to adult court.

Individually, each law punishes individuals that commit violent crimes with firearms. TIS restricts good time, while firearm enhancement increases time served. On top of this, automatic transfer makes even juveniles eligible for these harsher punishments (and don’t forget, Illinois doesn’t have parole).

That means that until a few years ago, a judge would have no choice but to sentence a 17-year-old who convicted of stealing $250 in an armed robbery—during which he or she fires a bullet into the ground—to be sentenced to no less than 26 years, of which at least 22 must be served. Specifically, after being automatically transferred to adult court due to the nature of the crime, the seventeen-year-old defendant would face a minimum of 6 years for armed robbery plus a mandatory 20 years added for the firearm enhancement. The entirety of this 26 years would be subject to TIS.

Recently, the policy has received some reform-minded attention. In 2016, the Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform—a bipartisan commission established by Governor Bruce Rauner to develop strategies to reduce the prison population in Illinois—called out TIS as one area in need of reform. You can read more about why the Commission called for a rollback of TIS in their final report (see recommendations #18 and #19).

Unfortunately, neither of these recommendations were realized to any substantial degree.

Linked Sources

Heaton, R. et al. (2016, December). Final report of the Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform. Chicago, IL. Retrieved from http://www.icjia.state.il.us.