What is retroactivity?

When it comes to criminal legal policy, the word “retroactivity” means applying new legislation to previous cases—to people who have already been sentenced. A retroactive law is “a legislative act that looks backward or contemplates the past, affecting acts or facts that existed before the act came into effect” (Black’s Law Dictionary, 7th Edition, pg. 1318).

In essence, this means retroactive laws change the legal consequences or status of past actions; theoretically, they can increase, decrease, or eliminate legal sanctions (length of sentences, sentence enhancements, etc.). However, both federal and Illinois law prohibits retroactive laws that increase penalties or impose new consequences on past actions.

Is retroactivity legal?

In the American legal system, the legality of a retroactively applied law depends largely on whether the law would improve or worsen the plight of the individuals it would affect. If it’s the latter, the law is known as an “ex post facto” law and is prohibited by the United States and Illinois constitutions.

However, neither constitution prohibits laws that retroactively remove or reduce the burden placed on people who have already been sentenced.

This distinction isn’t an oversight, but a vital feature of our justice system. The executive powers of pardon, commutation, and clemency are perhaps the clearest examples of our founding fathers’ acknowledgement that courts sometimes make mistakes and that finality in sentencing is ultimately less important than ensuring fair and proportionate justice.

This distinction goes back as far as 1798, when the United States Supreme Court ruled in the precedent-setting Calder v. Bull that every “ex post facto law must necessarily be retrospective, but every retrospective law is not an ex post facto law [and] the former only is prohibited.” The Court continued, writing, “There are cases in which laws may justly, and for the benefit of the community and also of individuals, relate to a time antecedent to their commencement, as statutes of oblivion or of pardon…[moreover] there is a great and apparent difference between making an unlawful act lawful and the making an innocent action criminal and punishing it as a crime” (Calder v. Bull, 1798).

What types of retroactive laws do reformers advocate for today?

Retroactive reforms today are designed to provide relief to individuals who have been disadvantaged by anachronistic, overly broad, vague, harsh, and/or disproven policies of the past.

While the damage inflicted by these policies can not always be undone through retroactive legislative reform, there are some policies where retroactivity makes a substantial difference. In some cases, new laws can effectively reduce sentence lengths or lessen rigid sentencing mandates that have led to over-incarceration.

Retroactivity is critical to sentencing reform because only retroactive reforms can help people whose ongoing sentences were imposed under extreme sentencing regimes, and it is the only way to reduce disparities in sentence lengths for similar offenses.

In Illinois, extreme, disproven, or overly broad sentencing policies include:

-

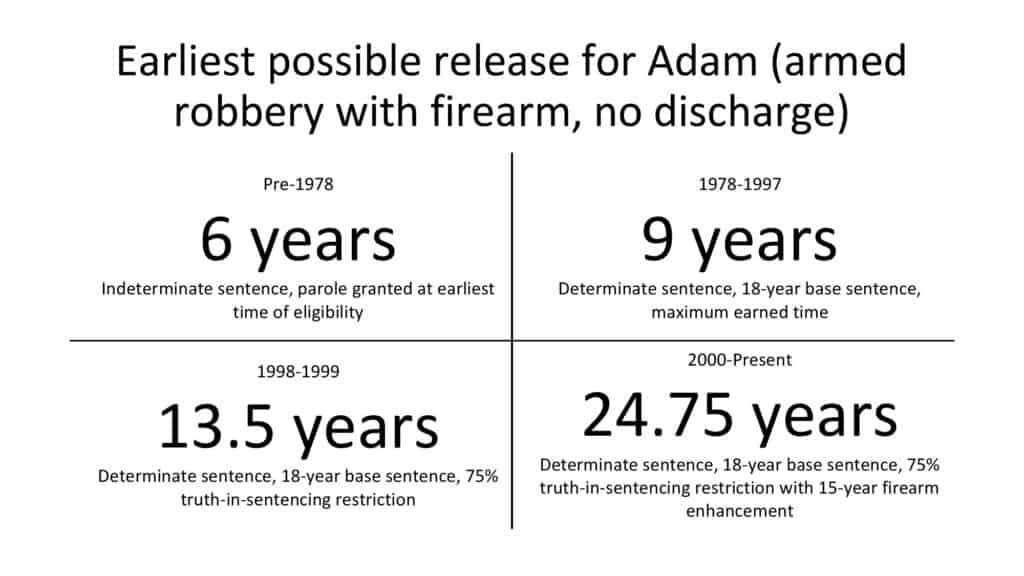

- Truth in sentencing (TIS)

- Laws that restrict parole and good conduct credit eligibility

- Classification of offenses and mandatory minimums

- Automatic transfer of juveniles to adult court

- Firearm enhancements

- Felony-murder reform

- The law of accountability

Why is retroactive criminal justice reform important?

To understand why meaningful reforms should be retroactive, consider the nearly 2,000 people who are serving sentences of 40 years or longer in the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) for things they were convicted of doing before their brains fully matured. By enacting legislation that would retroactively correct these extreme sentencing policies, we can make the legal system fairer and significantly reduce our prison population.

The Youthful Parole Bill (now Public Act 100-1182), which took effect on June 1, 2019, is an example of a law that would have had more impact if applied retroactively. The bill was signed into law by Governor JB Pritzker on April 1, 2019 and is an important first step in providing meaningful opportunities for rehabilitation and release. Illinois had abolished parole in 1978, and was one of just 16 states without such a system. The Youthful Parole law creates mid-sentence parole consideration for some incarcerated people who were under the age of 21 when the crimes they were convicted of occurred.

The law aligns with multiple U.S. Supreme Court decisions that charge states with viewing youthful offenders as “categorically less culpable” for their crimes. The Court has established those convicted in their youth should have meaningful opportunities for release. But, because this bill is not retroactive, it leaves out hundreds of people. A teenager sentenced to 40 years in 2018 will have to serve every single one of those years, whereas, a teenager convicted of the same crime in 2020 will have the opportunity to earn release.

Also consider the 2015 law, now Public Act 99-0069, that made firearm enhancements discretionary for individuals under the age of 18. Previously, judges were required to add 15 years to a child’s sentence if they simply possessed, but never used, a gun during the commission of a felony. Judges were mandated to add 20 years if the gun was used to inflict injury but not death and 25 years if the youth killed someone with the gun.

In the first year HB2471 was law, judges departed from applying the sentencing enhancement in 14 out of 16 homicide cases involving firearms and youth defendants. However, the new law was not applied retroactively, leaving hundreds of people without any relief. Again, because the law is not retroactive, it creates a huge discrepancy between youth convicted of the same exact crime but sentenced in different years.

What retroactive reforms could Illinois adopt to significantly reduce harm done by past policies?

-

-

- Roll back, lessen, or eliminate truth in sentencing for certain or all offenses.

- Introduce laws that increase or expand good time eligibility.

- Roll back, lessen, or eliminate firearm enhancements.

- Downgrade the classification of certain offenses (e.g., from Class 2 to Class 3).

- Lessen or eliminate mandatory minimums for certain or all offenses.

- Introduce laws that increase or expand parole eligibility.

-

For individuals serving long, mandatory sentences, this need is especially dire.

Where else in the U.S. have retroactive reforms been passed?

In recent years, other states have passed retroactive reforms to their criminal legal policies. Here are a few examples:

-

-

-

- In 2017, Louisiana passed a 10-bill package of criminal justice reforms, some of which applied retroactively. These include:

- Restoration of parole eligibility for individuals convicted of second-degree murder who have served 40 or more years

- Granting of parole eligibility under certain conditions to youth offenders sentenced to life for first- or second-degree murder who have served at least 25 years

- Grants medical treatment furlough to incarcerated persons with limited mobility

- In 2016, Colorado retroactively granted early release time to youth sentenced as adults for Class 1 felonies.

- In 2016, Delaware retroactively reformed its “three strikes law,” allowing people convicted under the law to petition for sentence modification after serving their mandatory minimum sentence.

- In 2016, Maryland reduced the permissible sentences for various drug-related and other offenses classified as “nonviolent,” allowing individuals incarcerated for those offenses to seek retroactive sentence reductions.

- In 2015, Nevada passed a retroactive law that abolished life without the possibility of parole sentences for most juvenile offenders and offered those individuals eligibility for parole review after 15 or 20 years served.

- In 2017, Louisiana passed a 10-bill package of criminal justice reforms, some of which applied retroactively. These include:

-

-

Why is it difficult to pass retroactive legislation?

There are individuals and organizations, particularly in law enforcement communities, who express concern that retroactive application of the law violates our state constitution. They argue it is a violation of the Illinois Constitution’s separation of powers provision. Accordingly, they believe the only lawful way to change or modify a criminal sentence 30 days or more after it was imposed is through executive clemency or a legal procedure called revestment (see below for more information), and they have convinced some legislators this is the law. However, this position is not supported by the law, as proven by a legal analysis.

Another reason retroactive legislation is difficult to build support for politically is because opponents believe it is unfair to victims and their families who are said to have been promised a particular sentence. While this argument may be compelling, it is less so when balanced against both the fundamental unfairness of requiring people to serve vastly different sentences for the same offense, and society’s duty to correct laws and policies that have been determined to no longer reflect “evolving standards of decency.”

What is Revestment?

Even though solid legal analysis of Illinois law finds the Illinois General Assembly can constitutionally enact retroactive legislation, opponents of retroactive reform point to something called “the revestment doctrine” as the core of their argument against retroactivity.

Generally, in both criminal and civil matters, a decision is considered final and the circuit (read: lower) court loses jurisdiction (read: authority) to hear or modify a final judgment 30 days after the judgement was entered. Revestment is an exception to this 30-day rule. In certain circumstances, the revestment doctrine allows a court to modify a final judgment after it has lost jurisdiction.

In an Illinois criminal proceeding, in order to revest (read: give back) the court with power to hear or modify a judgement after that 30-day period, the prosecution and the defense must: (1) actively participate in the subsequent proceedings; (2) fail to object to the untimeliness of the motion or petition filed in the subsequent proceeding; and (3) assert positions that are inconsistent with the merits of the prior judgment and support setting aside some portion of that judgment.

In simpler terms, revestment applies in individual cases when, generally, both the prosecution and the defense agree to change something about the final order and act as if the court has not lost jurisdiction. Revestment is inapplicable when the legislature seeks to change a sentencing law because it is a mechanism designed to be used in judicial proceedings, not by the legislature.

But, while there are no constitutional or statutory provisions that specifically grant the legislature the authority to enact laws that modify criminal judgments after 30 days, the Illinois Supreme Court has upheld the constitutional power of the Illinois Legislature to adopt statutes that permit people in certain circumstances to return to court more than 30 days after sentencing to seek to have their sentences reduced or otherwise altered.

In People v. Bainter, the Illinois Supreme Court upheld, as constitutional, statutory provisions that allow defendants sentenced in Illinois and other state or federal courts to return to court (in Illinois) to seek to have their sentences served concurrently. “The 30-day rule is not a constitutional mandate, and, as a rule of the common law, is susceptible to amendment by the legislature,” the Court explains (Id. 533 N.E.2d 1070). Past legislative enactments and judicial decisions should give the Illinois Legislature confidence to utilize its constitutional powers to enact retroactive legislation.

Here are other Illinois statutes that allow courts to modify judgments after 30 days:

-

-

-

- The Post-Conviction Hearing Act allows courts to grant defendants new trials in certain circumstances (725 ILCS 5/116-1).

- Circuit courts can terminate the wardship of juveniles at any time (705 ILCS 405/2-31(2)).

- Circuit courts can terminate a defendant’s probation or conditional discharge at any time (730 ILCS 5/5-6-2(c)).

- Circuit courts can revoke a sentence of periodic imprisonment at any time; circuit courts retain jurisdiction over defendants and may reduce sentences (730 ILCS 5/5-7-2, 730 ILCS 5/5-7-7).

- Circuit courts can modify maintenance and support orders post-judgment in dissolution of marriage cases (750 ILCS 5/510).

-

-

The case law is clear; the Illinois Legislature can legally enact retroactive sentencing reform.