Something Beyond Necessary

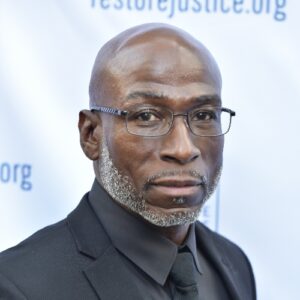

Joseph L. Moore Jr. is a graduate of the Restore Justice Future Leaders Apprenticeship Program. Joseph wrote the following essay during the fall of 2018 while incarcerated at Hill Correctional Center toward the end of his 26-year prison term.

By: Joseph L. Moore Jr.

By: Joseph L. Moore Jr.

Every Illinois prisoner should be eligible to earn meritorious “good time” because there’s no benefit to the prison system nor to public safety in denying people who are incarcerated an incentive to earn their release. In fact, being that most prisoners in the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) will one day be released, IDOC is essentially endangering the public by not offering a more robust system of all-inclusive meritorious good time that lets people focus on their rehabilitation.

All-inclusive meritorious good time encourages prisoners to enlist in behavioral modification and life skills courses, and will reduce the prison population and improve public safety. People who can earn time off their sentences are encouraged to learn, take courses that will help them better navigate life, and hone job skills. Therefore, if the purpose of prison is to modify behavior and improve public safety, good time is the means by which Illinois could arrive at its desired goals.

In the absence of an incentive for people who are incarcerated to participate in rehabilitative programs, some prisoners are left without a reason to undertake the arduous task of swimming against the tide of the current prison culture of violence and regression. In conjunction with the corrosive psychological, emotional, and physical aspects of incarceration, serving a protracted sentence of 20, 30, or 40 years further relegates many prisoners beyond the realm of self-sufficiency to the extent that upon release – many at 50, 60, even 70 years of age – they essentially move from one form of an all-encompassing tax burdening social program, prison, to another, public aid. Therefore, in most cases, without the incentive of meritorious good time, and the behavioral modification and life skills that will be taught therein, many prisoners will leave prison no-better-off, and in some cases worse, because of the trauma, than when they entered.

While the public has been indoctrinated by decades of pro-punishment rhetoric, the fact is longer, harsher sentences don’t reform prisoners nor do they make the public safer. There are numerous independent studies that reveal that the benefits that can be reaped by incarceration begin to wane after someone serves more than 10 consecutive years in prison, and, in fact, become detrimental to the rehabilitation process. Being that independent scientific research has revealed that there’s no real benefit to public safety nor to prisoners for keeping then incarcerated longer than 20 years, we must ask ourselves, “Why do we, as a society, continue to do it? Do we feel people owe a debt to society?”

Contrary to popular belief, while many of us are being warehoused in dilapidated 6×9 foot cells left withering away, and as horrible as the confines and accommodations are – leaky toilets, moldy showers, unsavory food – we aren’t paying a debt to society. Instead, we’re continuing to incur debt, financially and in the form of human capital, that we as a society can’t afford. Thirty years ago, Illinois spent $52 million annually on prisons; today it spends $1.4 billion.. The increase in prison spending is directly correlated to the increased length of, what we now know to be ineffective, prison sentences. These longer sentences have led to an inflated prison population. The human capital comes in the form of the 2.7 million children (under the age of 18) who have incarcerated parents. Twenty-three percent of those children have been expelled or suspended from school and have an increased risk of getting in trouble in their youth. This youthful interaction with law enforcement is a strong indicator of who will contribute to the future influx of prisoners; this is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

A system of all-inclusive meritorious good time will incentivize prisoners to comply with prison rules, which in turn will create a less violent and disruptive prison culture. As a result, the new prison culture will be conducive to the aim of rehabilitation. In the midst of that new culture, many prisoners could begin to truly repay their debts to society by securing release and employment while they are still relatively healthy and able-bodied enough to become members of the workforce. Being members of the workforce will enable them to establish relatively stable lives and become an active presence in their children’s lives, an act that will help stem the flow of the school-to-prison pipeline.

References

- Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform, Final Report (part 1 & 2) December 2016 p.8.

- The Pew Charitable Trust, 2010. Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect On Economic Mobility: Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trust.

- Johnson, Rucker C 2009 “Ever-Increasing Levels of Parental Incarceration and the Consequences for the Children” In Do Prisons Make Us Safer? The Benefits and Costs of the Prison Boom, ed Steven Raphael and Michael Stall, 177-206, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Travis, Jeremy, Elizabeth McBride, and Amy Solomon 2003; revised 2005 “Families Left Behind: The Hidden Cost of Incarceration and Reentry” Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.