Soon, the law may prevent someone in Jason Foster’s position from being charged with murder. But Jason and those already serving extreme prison sentences won’t benefit.

In January 2021, Illinois lawmakers passed extensive, multi-faceted legislation to address some of the most devastating, racially unjust practices that plague communities. Among its provisions, House Bill 3653, Senate Amendment 2 amends Illinois’s felony-murder law. It will likely prevent people from being charged with murder when a third-party kills their co-defendants; it should prevent people in Jason’s shoes from being charged with murder.

But, this part of the bill, like most sentencing reform legislation in Illinois, isn’t retroactive.

In 2010, Jason and his friends attempted to rob a pawn shop, Jason explained. An employee shot and killed Jason’s friend. Because Jason took part in the robbery, Illinois law allowed prosecutors to charge him with felony-murder for his friend’s death. A felony-murder conviction carries the same sentencing range as all first-degree murder convictions, a minimum of 20 years and a maximum of natural life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Like many young people facing decades in prison, Jason pleaded guilty and received a 20-year sentence. He has another 10 years left to serve. “Unfortunately, my friend’s life was taken, and, in a sense, so was mine. I’ve hurt, I’ve grieved, and I’ve mourned along with our families,” Jason said.

“I understand my actions and I’m not proud of them; in fact, I’m ashamed that I was easily influenced to make a poor decision that caused me to lose a friend and 10+ years of my life. I acknowledge my wrongdoings and sincerely apologize for my part in this,” Jason said. “(Still), it’s sad to know that even though I wasn’t responsible for my friend’s murder, I am held liable for it. I have been sentenced as if I actually committed a murder. The consequences are way too harsh and unjust!”

While in prison, Jason has sought every opportunity to better himself. He completed college courses in business. He obtained certifications in life skills courses. He consistently works and plays sports. “I use this time wisely to better myself as I look forward soon to reentering the world as a new man,” Jason said.

Here is Corey Trainor‘s story.

In 1997, a Cook County jury convicted Corey Trainor of felony-murder. Corey received a 60-year sentence and must serve at least 30 years.

Corey was just 19 years old when the crime happened.

Research has established the brain continues developing into our mid-20s, and the part of the brain that allows us to assess risk is among the last to form. “Research suggests emerging adults are more prone to risky and impulsive behaviors, more sensitive to immediate rewards, less future-oriented and more volatile in emotionally charged settings—psychological characteristics that mirror younger juveniles in some respects,” Harvard Kennedy School researchers explain.

There is growing recognition nationally and in Illinois that people in their late teens and early 20s should not be treated like older adults. In 2019, Governor JB Pritzker signed the Youthful Parole Bill, HB 531, into law, creating parole opportunities for some people younger than 21. This law created the first new parole opportunities in Illinois since the state eliminated the parole system in 1978, however, it is not retroactive so Corey cannot seek to show how he has changed since he was a teenager.

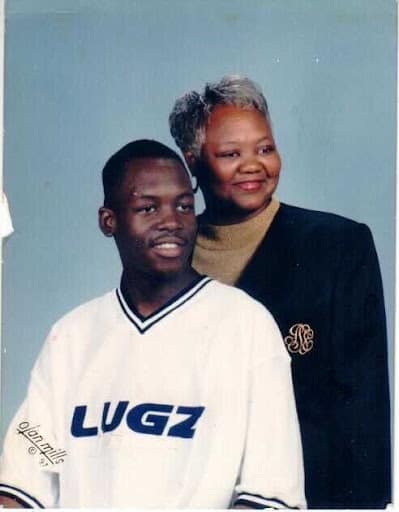

“Corey is remorseful and ready for leading society in the right direction. He has been educating himself,” Corey’s mom Johnnie said.

From prison, Corey received his GED and earned a spot on Lake Land College’s Dean’s List. He has completed a range of courses and participated in many programs, including conflict resolution, health-based classes, financial literacy training, and more. He’s now a Certified Master Shingle Applicator Wizard, Master Craftsman, and Insulation Master Craftsman, among other titles.

Corey is also a certified Master Gardener and he has a Private Pesticides License. He achieved these professional certifications through an intensive training program at Vienna Correctional Center. He learned about horticulture and small-farm management through a United States Department of Agriculture-funded program.

“What appeals to me is being able to grow my own fruits and vegetables, and possibly bring the skills I learn here to my neighborhood in Chicago,” Corey told Illinois Farmer Today. “I’d like to help improve the food selection.”

“Corey is ready to get out and use all of his potential to help take this economy to the next level. He has a lot of creativity locked up in him. Corey is looking forward to mentoring at-risk youth,” his mom said.

Corey grew up close to his immediate and extended family. They are still close-knit and want him home.

“Corey was a good son. He was always outspoken. His middle name, Shamar in Hebrew, means to protect, to guard, to watch, to save life, and to take charge. That’s Corey Shamar Trainer. His middle name speaks for itself,” Johnnie said.

In 2006, Christopher Carter received a 100-year sentence for his involvement in a crime that occurred when he was just 20 years old. Illinois law and that sentence mean Chris will die in prison, with no opportunity for a second chance, unless he receives some kind of clemency.

Cook County prosecutors charged Christopher through Illinois’s “Law of Accountability.” The state’s accountability law allows someone to be held responsible for a crime committed by another person. Someone could be charged through accountability if prosecutors say they failed to report the crime, acted as a lookout, or had other direct or indirect involvement. This law fails to account for whether an individual planned, agreed to, or intended to participate in the crime. In this case, the primary defendant took a plea deal and is actually serving a shorter sentence than Christopher.

The youngest of those charged in the case, Chris said he had prior no criminal record and was deemed the least culpable. “If sentences between (someone) convicted by accountability and (someone considered the principal) reflect the different degrees of participation in the crime, how is it that one can be given the same, if not more, time than the principal?” he questioned.

Illinois abolished parole in 1978 so no one sentenced after that year is eligible for parole review. In addition, in 1998, Illinois established “truth-in-sentencing,” meaning people convicted of certain offenses cannot receive any time off their sentences for good behavior or program participation. In other words, there are few real pathways for Chris to come home sooner.

Chris feels great remorse for the crime that occurred. He hopes his story will reach others at risk of being involved in a similar situation. Chris acts as a mentor for a university student. “My favorite part of being a mentor is being able to put myself, and all of the things that are going on in my life, to the side and being that someone that others can count on in their time of need,” he explained.

In prison, despite having no real pathway to come home, Chris has utilized his passion for woodworking and craftsmanship and continues trying to improve his skills. He remembers watching home remodeling and woodworking shows as a child in his parents’ bed on Sunday mornings. So, while incarcerated, he found a program to hone these interests into a real craft.

Chris hopes for a second chance so he can someday put the skills he has learned to use in order to benefit others. “All in all, just being able to give back is all the motivation,” he says.

Chris often speaks on the phone with his mom and he wishes he could better support her. “Chris is my baby. He is a good son, and I just want him to come home so he can take care of me,” his mom said.

In 1987, Winston McIntyre received a sentence of natural life in prison after being convicted of murder and armed robbery. He was just 24 years old.

Winston received this condemnation to die behind bars for a crime he did not actually commit; he was not even at the scene of the crime, which officials acknowledged in court. “The court said that I was being used by my co-defendant,” Winston explained. “The court knew and very well understood that I didn’t knowingly play a part in this crime.”

Yet, the State put Winston through a death penalty hearing and ultimately gave him that life sentence. “My case is clearly one that represents an unjust system,” Winston said.

This conviction is a result of Illinois’s law of accountability, which allows people to be charged and convicted of a crime they did not plan, agree, intend to commit, or commit. People can be convicted even if they were not at the scene. (The accountability law is related to felony murder, which lawmakers amended in February.)

Before his incarceration, Winston dropped out of high school to help provide for his mother and his four siblings. In prison, he received his high school diploma and college credit. He studied reading and creative writing at Menard Correctional Center—until the prison stopped providing such opportunities. After the educational programs were removed, Winston sought out correspondence programs he could do on his own. He has also encouraged and helped other people obtain their GEDs. Additionally, Winston has completed multiple religious programs and worked throughout his years in prison.

These accomplishments reflect Winston’s drive and commitment to bettering himself. When he arrived in prison, he sought to “find God and His Son, Jesus Christ as (his) Lord and Savior,” and seek “forgiveness and become a better man and person.”

Winston has now been in prison for more than 33 years. He hopes to one day live outside of prison as a free man. However, Illinois abolished parole in 1978 so there are few avenues for his release. It would take a gubernatorial clemency or judicial resentencing, both of which are not easy pathways; Winston has been denied clemency multiple times since 2010. Still, he continues to remain positive. “I’m always faithful and hopeful for tomorrow,” he said.